Cuban Journal of Forest Sciences. 2023; January-April 11(1): e783.

Translated from the original in spanish

Original article

Diversity of Trees and Shrubs in the Urban Parks of the City of Cintalapa de Figueroa, Chiapas, Mexico

Diversidad de árboles y arbustos en los parques urbanos de la ciudad de Cintalapa de Figueroa, Chiapas, México

Diversidade de árvores e arbustos em parques urbanos na cidade de Cintalapa de Figueroa, Chiapas, México

1El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR). México.

*Corresponding author:alexis.dominguez@posgrado.ecosur.mx

Received:2023-01-20.

Approved:2023-03-30.

ABSTRACT

The influence of trees in urban parks is a key element because they are sites of recurrence of citizens when carrying out activities of rest, recreation or simple leisure, allowing to release the stress of working days. However, the diversity and richness of tree and shrub species has generally been little analyzed by those responsible or in charge of green areas in municipal councils. Therefore, the objective of this study was to identify the tree and shrub species found in five urban parks in the city of Cintalapa de Figueroa in Chiapas, Mexico. Sampling and identification was developed in a single stage in all five parks. A total of 8 woody species belonging to 6 families and 7 genera were recorded, including shrubs (1 %) and trees (99 %). The families with the highest number of species were Bignoniaceae (22 %) and Meliaceae (16.6 %). The genera with the highest number of species in the parks were Tabebuia (71), Ficus (34) and Thuja (12). 40.96 % of species are introduced and 59.03% native. Among the species registered, Cedrela odorata L. is listed in "special protection" status according to NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010. Knowledge of the type of species found in urban parks is suitable for use in the design and selection of native trees and shrubs, both for production in municipal nurseries, and for subsequent planting.

Keywords: Urban ecology; introduced species; native species; urban biodiversity; Ecological indices.

RESUMEN

La influencia del arbolado en los parques urbanos es un elemento clave por ser sitios de recurrencia de los ciudadanos a la hora de realizar actividades de descanso, recreación o simple ocio, permitiendo liberar el estrés de las jornadas laborales. Sin embargo, la diversidad y riqueza de especies de árboles y arbustos por lo general, ha sido poco analizada por los responsables o encargados de las áreas verdes en los ayuntamientos municipales. Por ello, el objetivo del presente estudio fue identificar las especies arbóreas y arbustivas que se encuentran en cinco parques urbanos de la ciudad de Cintalapa de Figueroa en Chiapas, México. El muestreo e identificación se desarrolló en una sola etapa en los cinco parques. Se registraron 8 especies leñosas en total pertenecientes a 6 familias y 7 géneros, incluidos arbustos (1 %) y árboles (99 %). Las familias con mayor número de especies fueron Bignoniaceae (22 %) y Meliaceae (16.6 %). Los géneros con mayor número de especies en los parques fueron Tabebuia (71), Ficus (34) y Thuja (12). El 40.96 % de especies son introducidos y 59.03 % nativos. Entre las especies registradas, Cedrela odorata L. se encuentra catalogada en estatus de "protección especial" según la NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010. El conocimiento del tipo de especies que se encuentran en los parques urbanos es adecuado para su uso en el diseño y selección de árboles y arbustos nativos, tanto para la producción en viveros municipales, como para su posterior plantación.

Palabras clave: Ecología urbana; Especies introducidas; Especies nativas; Biodiversidad urbana; Índices ecológicos.

SÍNTESE

A influência das árvores nos parques urbanos é um elemento chave, pois são lugares onde os cidadãos vão para descanso, recreação ou simples atividades de lazer, permitindo-lhes aliviar o estresse do dia de trabalho. Entretanto, a diversidade e a riqueza das espécies de árvores e arbustos tem sido geralmente pouco analisada pelos responsáveis ou responsáveis pelas áreas verdes nos conselhos municipais. Portanto, o objetivo deste estudo foi identificar as espécies de árvores e arbustos encontrados em cinco parques urbanos da cidade de Cintalapa de Figueroa, em Chiapas, México. A amostragem e identificação foi realizada em uma única etapa nos cinco parques. Um total de 8 espécies lenhosas pertencentes a 6 famílias e 7 gêneros foram registradas, incluindo arbustos (1 %) e árvores (99 %). As famílias com o maior número de espécies foram Bignoniaceae (22 %) e Meliaceae (16, 6 %). Os gêneros com o maior número de espécies nos parques foram Tabebuia (71), Ficus (34) e Thuja (12). Os 40,96 % de espécies são introduzidos e 59,03 % são nativos. Entre as espécies registradas, Cedrela odorata L. está listada em status de "proteção especial" de acordo com o NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010. O conhecimento do tipo de espécies encontradas nos parques urbanos é adequado para uso no projeto e seleção de árvores e arbustos nativos, tanto para produção em viveiros municipais quanto para plantio posterior.

Palavras-chave: Ecologia urbana; Espécies introduzidas; Espécies nativas; Biodiversidade urbana; Índices ecológicos.

INTRODUCTION

Currently, an important part of sustainability regarding green areas in a city is related to the management and analysis of urban ecology, considered as an ecological metabolism when analyzing the flows and consumption of material resources and typical of the place, from different perspectives and interrelation with other fields of study (Cursach et al., 2012; Hahs and Evans, 2015). In this context, when a new human settlement (locality, colony or city) begins, processes of destruction and drastic change of the ecosystem also begin, losing sight of all the given ecological processes and the decrease of the biodiversity present in the place (Faeth et al., 2011).

However, despite the fact that cities, and not only in Mexico, but in the world, are home to a large number of people (with an exponential increase), green areas are and must be taken into account more and more as spaces for the conservation of biodiversity, especially native trees (Kowarik, 2011; Ramalho and Hobbs, 2012). With some investigations carried out in urban parks, they have sometimes observed that the diversity of trees present in these sites is high when they are in the city, finding an equality between the number of native and exotic species (McKinney, 2008). Therefore, urban parks designed as green sites have to be managed and intervened to improve the view and architecture of the landscape, since they are the spaces with the greatest accessibility and visits by the inhabitants of urbanized areas.

Part of the importance of urban parks in cities is given by the different environmental services they provide; from the mitigation and reduction of air pollution, noise reduction due to the constant traffic due to the use of motor vehicles, to scenic beauty, also favoring the conservation of biological diversity, both for the local flora and fauna (Miras et al., 2022; Ortiz and Luna, 2019; Cortazar, 2022). Among other functions that trees provide, they also mention the capture of pollutants found in the air or the atmosphere, the conservation of greater humidity in the soil through its root system and, mainly, that they are a key piece in the mitigation of climate change, being focal points in a site with a lot of construction or infrastructure around it, that is, key to environmental health in cities (Hinojosa, 2023; Orozco et al., 2020; Villafuerte, 2023).

The intervention of man in these spaces destined for scenic beauty and landscaping in a city is fundamentally direct and very transformative, since it has the power to change how an urban park is seen and perceived from the start, and may or may not have a good design for the inhabitants who visit it during their free time (Téllez, 2023; Zúñiga et al., 2023). Especially since they are places that must provide a natural environment, and that provide social and environmental benefits, allowing the same society to appropriate their spaces, their biological diversity as well as their native tree species (Ferrufino et al., 2018).

The objective of this study was to identify native and introduced tree and shrub species in five urban parks in the city of Cintalapa de Figuera, Chiapas, Mexico, used to reforest and beautify these spaces. The analysis was aimed at the identification of trees and shrubs, as well as the comparison of the richness and diversity of the sampled urban parks. With the above, it seeks to obtain useful information for future urban projects related to green areas in Cintalapa, Chiapas, in regards to the appropriate selection of species according to the space and area in which it is built in the region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

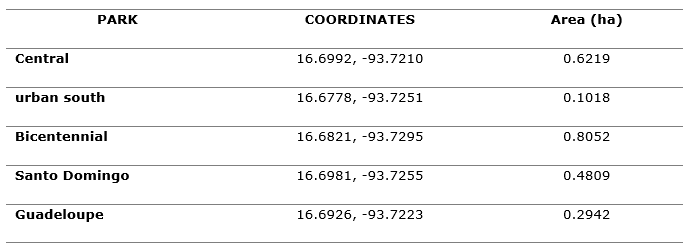

Study area. Five urban parks were visited in the city of Cintalapa de Figueroa, Chiapas, including Central, Santo Domingo, Guadalupe, Bicentenario and Sur Urbana parks (Table 1).

Table 1. - Characteristics of the five urban parks studied in Cintalapa de Figueroa, Chiapas

Data collection. The data collection was carried out in a single stage in the five parks, in which the sites were sampled with the support of an undergraduate student to distinguish the diversity of tree and shrub species in the parks. Specimens with flowers or fruits were collected for later identification in the ECOSUR-Tapachula Herbarium (ECO-TA-H) when necessary. The specimens were identified using dichotomous keys of the Mesoamerican Flora (Davidse et al., 1994) when necessary. Data on life form, origin of species and scientific names were consulted at World Flora Online (http://www.worldfloraonline.org). Information on common names and uses was collected from specialized literature and through consultation with local people when necessary. To identify the conservation status of the species in Mexico, the databases of the NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010.

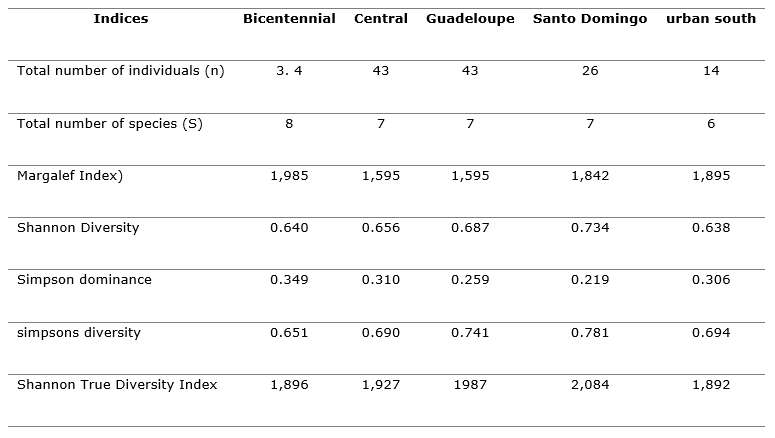

Analysis of the information. To evaluate the horizontal structure, richness and diversity, the total number of individuals (n) was determined; total number of species (S); specific richness (Margalef index) which is based on the quantification of the number of species present; alpha diversity (Shannon) which is based on the proportional distribution of abundance of each taxon (Magurran, 2004); Simpson dominance, Simpson diversity (1 Simpson dominance) and Shannon true diversity index (Jost, 2006). The formulas used to determine the diversity indices are shown in Table 2 (Table 2).

Table 2. - Formulas used to determine diversity indices

The diversity of species, in its definition, of each analysis and sampling considers both the number of species (richness) and the number of specimens (abundance) of each species (Mostacedo, 2000). The Shannon-Wiener index is the most widely used to determine the diversity of plant species in a given habitat, in this case parks. The results of this index are expressed as a positive number, which in most natural ecosystems varies between 0 and 1, but has no upper limit. This index was used because the sampling corresponds to a census, since all the trees in each park were considered and, consequently, all the specimens of the plant community are included in the sampling.

Statistical analysis. The data and information collected from urban parks were analyzed descriptively or with descriptive statistics; To facilitate observation and results, the data was recorded in Microsoft Excel® 2013 for Windows.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

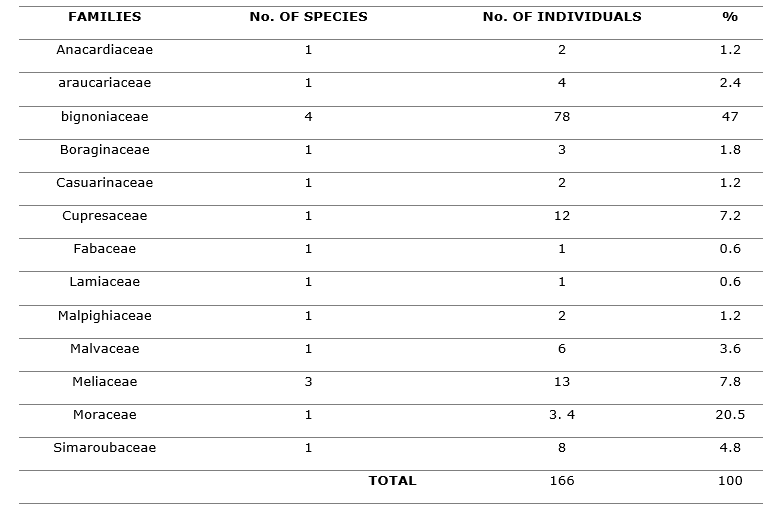

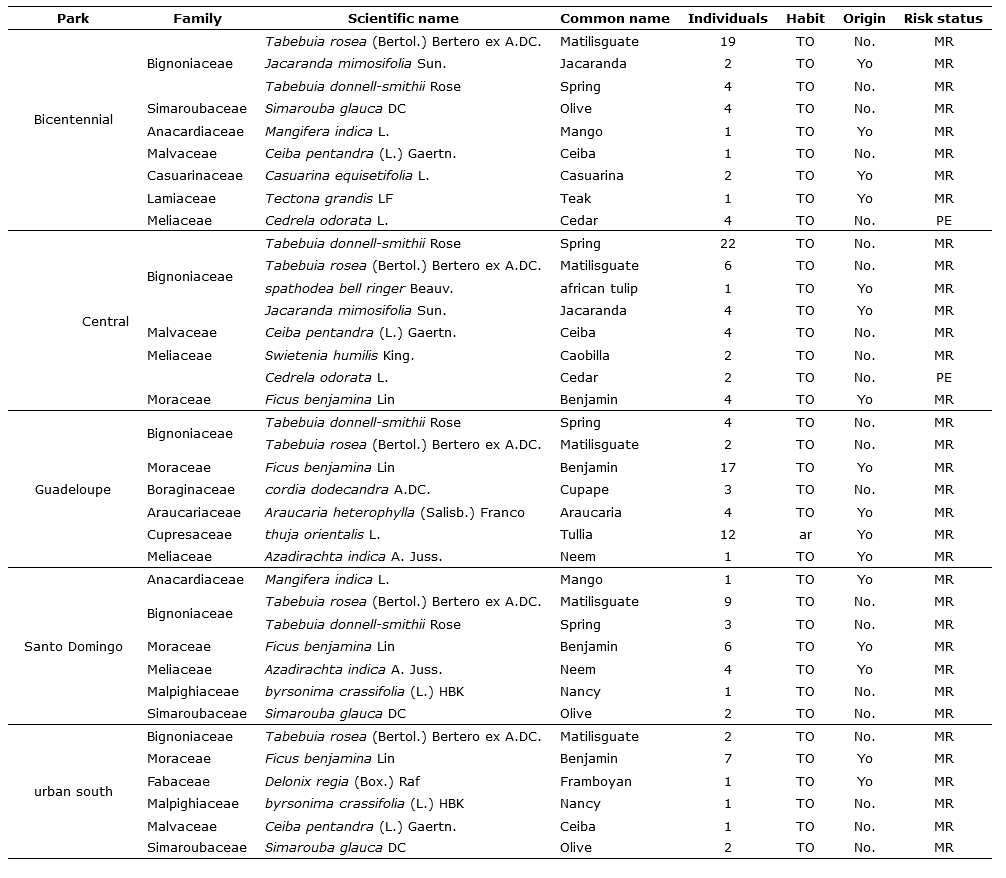

Eight different tree species were recorded, of which the total number was 35 species in the five urban parks, belonging to 6 families and 7 genera. The families with the highest number of species were Bignoniaceae (22 %) and Meliaceae (16.6 %). The genera with the highest number of species in the parks were Tabebuia (71), Ficus (34) and Thuja (12) (Table 3).

Table 3. - Families present in the urban parks of Cintalapa, Chis

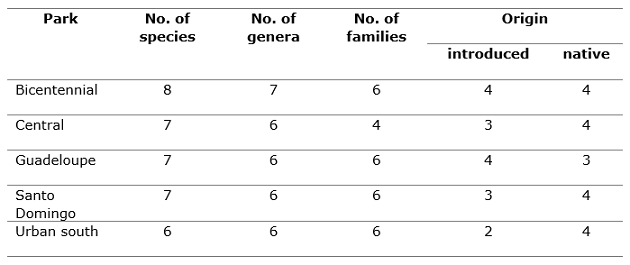

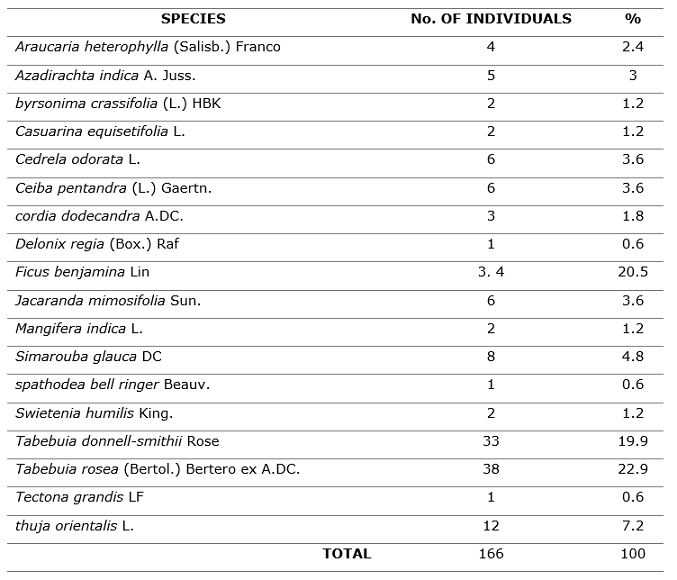

The Bicentennial Park shows the highest number of species (8), while the Central, Guadalupe, Santo Domingo and Sur Urbana, maintain the same number of species (7) (Table 4). The most common species, recorded in the five parks, were Tabebuia rosea (Bertol.) Bertero ex A.DC., tabebuia donnell smithii Rose, thuja orientalis L. and Jacaranda mimosifolia Dom. (Table 5). Of the species listed in the urban parks of Cintalapa, 59.03% are native and 40.96 % are introduced. The most common forms of life found were trees (99 %), and to a lesser extent shrubs (1 %) (Table 6). Similarly, Castillo and Pastrana (2015) state that the diversity of tree species, in their case, of alignment, presents this situation of kinship in the number of native species with respect to the introduced ones, due to the fact that there are deficiencies in environmental management and ignorance of other interesting species by the authorities and designers, as well as gardening fashions.

Table 4. - Floristic composition of the five urban parks studied in Cintalapa, Chis

Table 5. - Species found in the parks of Cintalapa, Chis

Table 6. - List of tree species of the important parks of Cintalapa de Figueroa, Chiapas, Mexico

Note: Origin (N = native; I = introduced). Risk status (SR = no risk; PE = special protection; A = threatened, P = Danger of extinction). Habit: A = tree, Ar = shrub.

Among the studies focused on the evaluation and identification of species present in urban parks in cities, there is that of Nelson (2004), who carried out a study in avenues and boulevards of the Municipality of the Central District, Honduras, identifying the number of species native and introduced, focusing on rare and vulnerable plants that he could find. Similarly, Ferrufino et al. (2015) carried out an observation on the flora in the Ciudad Universitaria campus of the National Autonomous University of Honduras.

In "special protection", according to NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010, there is Cedrela odorata L. with 6 individuals found in urban parks, while the rest of the species are registered as "without risk". For his part, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) considers the red cedar in the vulnerable category (VU), while in CITES, it is found in Appendix II, which states that it is not necessarily threatened with extinction, but could become so unless its trade is strictly controlled. The largest number of tree individuals was recorded in Central and Guadalupe Park (43), followed by Bicentennial Park (34). While in the total number of species, Bicentenario (8) preserves a greater number than the rest of the parks, the difference between the others is one species (6-7). The specific richness found in the Bicentennial Park was the most outstanding (1.98) among the parks, Sur Urbana was the second most rich in species. In alpha diversity by Shannon, Santo Domingo (0.73) where a higher diversity index was found, followed by Guadalupe Park (0.68). Simpson's record of greatest dominance was in the Bicentennial, the least was in Santo Domingo. However, in Simpson's diversity, the highest index was for Santo Domingo, followed by Guadalupe. The lowest true diversity index for Shannon was for the Sur Urbana Park, and the one with the highest index was for Santo Domingo (Table 7).

In an example regarding invasive alien species that can be found in some urban parks, Román-Guillen et al. (2019) identified in green spaces in the city of Tuxtla Gutiérrez that among the hundred most harmful species in the world that the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) cites, they found present in such green spaces: guarumbo (Cecropia peltate), gourd (Leucaena leucocephala) and African tulip (Spathodea, campanulata) (Lowe, Browne, Boudjelas & De Poorter, 2004). They also recorded other species such as angel hairs (Albizia lebbeck), cow's foot (Bauhinia variegata), cañafistula (Cassia fistula), flamboyant (Delonix regia), tamarind (Tamarindus indica), paradise (Melia azedarach), gooseberry (Phyllanthus acidus) and orange (Citrus sinensis), identified as invasive species in Mexico by the National Commission for the Use and Knowledge of Biodiversity (CONABIO) (2016).

Among the exotic or introduced species found in the present work, are; jacaranda mimosifolia Sun, Mangifera indica L., Casuarina equisetifolia L., Tectona grandis LF, Spathodea bell ringer Beauv., Ficus benjamina Lin , Araucaria heterophylla (Salisb.) Franco, Thuja orientalis L., Azadirachta indica A. Juss. and Delonix regia (Boj.) Raf, number of species that are probably very alarming due to the number of individuals found, however, their frequency should be considered when carrying out and validating management plans or replanting of trees in areas urban areas with parks in Cintalapa and nearby places.

Table 7. - Diversity indices evaluated in the urban parks of Cintalapa, Chis

The origin of the trees and shrubs observed in our sites is similar, since in general it can be mentioned that there are 50-50 % of native and introduced species, despite this, the species present should be mostly native or local, since they have some advantages: adaptation to the climatic, soil, geological and water conditions of the place of origin; seeds or propagules are locally available; conservation of the heritage and genetic diversity; provide habitat for local wildlife; they tolerate diseases and pathogens (pests) and identity with the environment of the city, it is native vegetation (Alvarado et al., 2023; Cajilema and Fernández, 2023).

Canizales et al. (2020) reported in an urban park in the city of Montemorelos, Nuevo León, northeastern Mexico, a total of 918 trees of 13 species, belonging to 11 genera, of which seven are introduced, a lower number than that found in our research; They also reported a Margalef (D) index of 1.9, a Shannon (H') diversity of 1.17 and a Real Diversity Index of 3.22. Alanís-Rodríguez et al. (2022), mentioned in their work carried out in the urban park in the center of Hualahuises, Nuevo León a record of 38 species of vascular plants distributed in 35 genera and 22 families. 63.20 % (25 species) are introduced and 36.8 % (21 species) are native. The most representative family was Fabaceae with four species. However, Terrazas et al. (1999), Zamudio (2001), Velasco et al. (2013) and Sánchez and Artavia (2013) show that, based on their research, urban green areas in cities and in general, urban floristic diversity in the country is poor, so it is necessary to establish new research to contemplate such important spaces.

Yulibeisi et al. (2022) evaluated the floristic description and a diagnosis of the situation of trees in the urban area of the city of El Vigia, Merida Venezuela. They found 634 individuals distributed in 13 families, 30 genera and 31 species, 38.70 % of which were introduced. The most representative species was Moquilea tomentosa with 18.24 % (IVI Importance Value Index). They observed that there was a predominance of individuals on the sidewalks with 215 (33.91 %), followed by the islands on the avenues with 194 (30.59 %), other locations with maintenance with 117 (18.4 5 %) and patios with 108 (17.03 %). The authors confirm the importance of the role that trees play in cities, as well as highlight the obvious damage that is caused to nature due to poor planning of urbanism and its green areas, a case similar to what was found in the present work of investigation.

The spaces for green areas in urban parks in Cintalapa, Chis., despite the lack of organization and distribution of species in each of the parks, these form and are an important part of the health and quality of life of the inhabitants of the city (Martínez et al., 2020), but lacking interest from them as they do not get involved in the green areas of the parks.

CONCLUSIONS

It is concluded that the diversity of trees and shrubs presents a low diversity and richness in the parks due to the lack of planning.

From the identification of the species in the urban parks, it is possible to address replanting proposals with native tree species from the Cintalapa Valley (low deciduous forest) with those already existing in the urban parks, in order to reduce and control the number of species introduced in the spaces dedicated to free time and interaction of the population.

THANKS

The author is especially grateful to C. Martín A. Domínguez for his accompaniment and collaboration in carrying out this study in the parks of Cintalapa, Chis.

REFERENCES

ALANÍS-RODRÍGUEZ, E., MORA-OLIVO, A., MOLINA-GUERRA, V. M., GÁRATE-ESCAMILLA, H. y SIGALA RODRÍGUEZ, J. A. 2022. Caracterización del arbolado urbano del centro de Hualahuises, Nuevo León. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales vol 13 no. 73. Recuperado de DOI: 10.29298/rmcf.v13i73.1271.

ALVARADO, R. J. G., CEPEDA, M. K. C., BUSTAMANTE, P. D. Y. y PALACIOS, A. J. P. 2023. Incidencia de la tala de árboles producto de la regeneración urbana en el bienestar de los pobladores del cantón Babahoyo. Estudios del Desarrollo Social: Cuba y América Latina 11 (Especial No. 1): pp. 79-88. Recuperado de https://revistas.uh.cu/revflacso/article/view/2733.

CANIZALES VELÁZQUEZ, P. A., ALANÍS RODRÍGUEZ, E., HOLGUÍN ESTRADA, V. A., GARCÍA, S. Y CHÁVEZ COSTA, A. C. 2020. Caracterización del arbolado urbano de la ciudad de Montemorelos, Nuevo León. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales vol 11 no. 62. Recuperado de DOI: https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v11i62.768.

CASTILLO, L., y PASTRANA, J. C. 2015. Diagnóstico del arbolado viario de El Vedado: composición, distribución y conflictos con el espacio construido. Arquitectura y Urbanismo vol. 36 no.2: pp. 93-118. Recuperado de: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=376839254007

CAZALES VELÁZQUEZ, P. A., ALANÍS RODRÍGUEZ, E., HOLGUÍN ESTRADA, V. A., GARCÍA GARCÍA, S. y CHÁVEZ COSTA, A. C. 2020. Caracterización del arbolado urbano de la ciudad de Montemorelos, Nuevo León. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales vol. 11 no. 62. Recuperado de DOI: https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v11i62.768

COMISIÓN NACIONAL PARA EL USO Y CONOCIMIENTO DE LA BIODIVERSIDAD (CONABIO). 2016. Sistema de información sobre especies invasoras en México. Recuperado de http://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/invasoras.

CURSACH, J. A., RAU, J. R., TOBAR, C. N. y OJEDA, J. A. 2012. Estado actual del desarrollo de la ecología urbana en grandes ciudades del sur de Chile. Revista de Geografía Norte Grande 52: pp. 57-70. Recuperado de https: www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0718-34022012000200004

DAVIDSE, G., SOUSA, M. S. y CHATER, A. O. 1994. Flora Mesoamericana (en línea) Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Instituto de Biología, Missouri Botanical Garden, Natural History Museum (London, England) UNAM. Recuperado de https://tropicos.org.

FAETH, S. H., BANG, C. y SAARI, S. 2011. Urban biodiversity: patterns and mechanisms. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences vol. 1223 no. 1: pp. 69-81. Recuperado de https://doi.org/10.1111/j.17496632.2010.05925.x.

FERRUFINO, L., OYUELA, O., RUBIO, A., SANDOVAL, G. y SOSA, E. 2018. El Jardín Botánico del Centro de Interpretación Ambiental Felipe II: Un espacio para conservar la flora urbana de Francisco Morazán. Revista Ciencia y Tecnología 23: pp. 60-80. https://www.camjol.info/index.php/RCT/article/view/6861

FERRUFINO, L., OYUELA, O., SANDOVAL, G. y FRANCIA BELTRÁN, F. 2015. Flora de la ciudad universitaria, UNAH: un proyecto de ciencia ciudadana realizado por estudiantes universitarios. Revista Ciencia y Tecnología 17: pp. 112-131. Recuperado de DOI: https://doi.org/10.5377/rct.v0i17.2684.

HAHS, A. K. y EVANS, K. L. 2015. Expanding fundamental ecological knowledge by studying urban ecosystems. Functional Ecology 29: pp. 863-867. Recuperado de DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12488.

HINOJOSA, M. I. 2023. Propuesta de Planificación de Parques Verdes Sostenibles, en el Polígono de Metro Park, Corregimiento de Juan Díaz, Distrito de Panamá. In Gobernanza, comunidades sostenibles y espacios portuarios (pp. 1085-1100). Servicio de Publicaciones, Universidad de Huelva.

JOST, L. 2006. Entropy and diversity. Oikos vol. 113: 110-116. DOI: Recuperado de 10.1111/j.2006.0030-1299.14714.x.

MAGURRAN, A. E. 2004. Measuring biological diversity. Blackwell Publishing. Oxford, UK. 215 p. Recuperado de http://www.bio-nica.info/Biblioteca/Magurran2004MeasuringBiological.pdf

MARTÍNEZ-VALDÉS, V., RIVERA EVODIA, S., GONZÁLEZ GAUDIANO y EDGAR J. 2020. Parques urbanos: un enfoque para su estudio como espacio público. Intersticios sociales no. 19: pp. 67-86. Recuperado de http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2007-49642020000100067&lng=es&tlng=es.

MCKINNEY, M. L. 2008. Effects of urbanization on species richness: a review of plants and animals. Urban ecosystems vol. 11 no. 2: pp. 161-176. Recuperado de DOI: 10.1007/s11252-007-0045-4.

MIRAS, M., et al. 2022. Los unos y los otros. Anales del IAA vol. 52 pp. 1. 1-4 pp. Recuperado de: http://www.iaa.fadu.uba.ar/ojs/index.php/anales/article/view/425/699

MOSTACEDO, B. 2000. Manual de métodos básicos de muestreo y análisis en Ecología Vegetal. BOLFOR. Santa Cruz, Bolivia. 92 p. Recuperado de https://www.bio-nica.info/biblioteca/mostacedo2000ecologiavegetal.pdf

NELSON, S. C. 2004. Vegetación en el ámbito urbano. Tegucigalpa, 76 p.

OROZCO, M., MARTÍNEZ, J., FIGUEROA, A. y DAVYDOVA, V. 2020. Environmental Health Diagnosis in a Park as a Sustainability Initiative in Cities. Sustainability 12:64-36. Recuperado de https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343555560_Environmental_Health_Diagnosis_in_a_Park_as_a_Sustainability_Initiative_in_Cities

ORTIZ, N. L., y LUNA, C. V. 2019. Diversidad e indicadores de vegetación del arbolado urbano en la ciudad de Resistencia, Chaco - Argentina. Agronomía y Ambiente vol 39 n. 2: pp. 54-68. Recuperado de http://agronomiayambiente.agro.uba.ar/index.php/AyA/article/view/97

RAMALHO, C. E. y HOBBS, R. J. 2012. Time for a change: dynamic urban ecology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution vol 27 no. 3: pp. 179-188. Recuperado de https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2011.10.008.

ROMÁN-GUILLÉN, L. M., ORANTES-GARCÍA, C., CARPIO-PENAGOS, C. U., SÁNCHEZ-CORTÉS, M. S., BALLbKINAS-AQUINO, M. S. y FARRERA SARMIENTO, O. 2019. Diagnóstico del arbolado de alineación de la ciudad de Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas. Madera y Bosques vol. 25 no. 1: e2511559. Recuperado de DOI: 10.21829/myb.2019.2511559.

SÁNCHEZ, G. y ARTAVIA, R. 2013. Inventario de la foresta en San José: gestión ambiental urbana. Ambientico , pp. 26-33. DOI: https://www.ambientico.una.ac.cr/wp-content/uploads/tainacan -items/5/24175/232-233_26-33.pdf

VELASCO, E., CORTÉS, E., GONZÁLEZ, A., MORENO, F. y BENAVIDES, H. 2013. Diagnóstico y caracterización del arbolado del Bosque de San Juan de Aragón. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales vol. 4 no. 19, pp. 102-111. https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2007-11322013000500009

VILLAFUERTE, G. R. V. 2023. La regeneración de áreas verdes y urbanas en los Altos de Chiapas. Revista Latinoamericana de Investigación Educativa ReLIE vol 1 no. 3: 39.

YULIBEISI, D., PINO, M., RONALD, R., QUINTANA, L. M y GÓMEZ, A. 2022. Caracterización florística y condición actual del arbolado urbano, El Vigía, Mérida Venezuela. Recursos Rurais 18: 17-30 ISSN 1885-5547 - e-ISSN 2255-5994. Recuperado de https://doi.org/10.15304/rr.id8568.

ZÚÑIGA, N. C., MORA, E. C. y CHAVES, K. B. 2023. Parques públicos regionales, GAM, Costa Rica: patrones de uso y percepciones de personas usuarias. Ingeniería: Revista de la Universidad de Costa Rica vol. 33 no. 3: pp. 99-106. Recuperado de https://www.kerwa.ucr.ac.cr/handle/10669/88052

Conflict of interests:

The authors declare not to have any interest conflicts.

Authors' contribution:

The authors have participated in the writing of the work and analysis of the documents.

![]()

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0

International license.

Copyright (c) Alexis Domínguez

Liévano