Cuban Journal of Forest Sciences. 2023; January-April 11(1): e772.

Translated from the original in spanish

Original article

Floristic inventory in two agroforestry systems of the San Francisco enclosure of the El Anegado parish

Inventario florístico en dos sistemas agroforestales del recinto San Francisco de la parroquia El Anegado

Inventário florístico em dois sistemas agroflorestais do recinto San Francisco da freguesia de El Anegado

Alfredo Jiménez González1*![]() , Roberth Joshua Carvajal Nunura1

, Roberth Joshua Carvajal Nunura1 ![]() , Jahir Aníbal Ponce

Muñiz1

, Jahir Aníbal Ponce

Muñiz1![]() , César Alberto Cabrera

Verdesoto1

, César Alberto Cabrera

Verdesoto1![]() , Jesús De los Santos Pinargote

Choez1

, Jesús De los Santos Pinargote

Choez1![]()

1Southern Manabí State University. Ecuador.

*Corresponding author: alfredo.jimenez@unesum.edu.ec

Received:2022-09-23.

Approved:2023-03-20.

ABSTRACT

Agroforestry systems are an alternative land use and constitute a combination of agronomic and forest species. With the objective of characterizing the agroforestry systems of the San Francisco enclosure of the El Anegado parish, a floristic inventory was carried out and information was collected on the use and management of the components of the farms, between February and March, 2022; Margalef, Simpson, Shannon and Pielou Equity diversity indices were calculated. Among the inventoried species, Coffea arabica L., Handroaunthus billbergii (Bureau & K. Schum.) S. O. Grose and Theobroma cacao L. stand out; while, Cedrela montana Moritz ex Turcz.; Cecropia maxima Snethl. and Handroanthus chrysanthus (Jacq.) SO Grose, are categorized as vulnerable. In the El Palmital farm, food use predominates (54.55%) and in La Fortuna, timber prevails (51.72 %). The diversity indices in both farms showed high, medium and low values, according to the Margalef, Simpson and Shannon indices, respectively. The largest use of land in El Palmital is the planted area 74.23% (1.80 ha) and in La Fortuna the non-agricultural area dominated 55.88 % (0.95 ha). The characterization of agroforestry systems provides a better view of them, by conducting inventories of species that reflect their importance, management and organization, allowing redesign and optimization of their operation.

Keywords: Floristic inventory; indices; diversity; redesign; farms.

RESUMEN

Los sistemas agroforestales son una alternativa del uso de tierra y constituyen una combinación de especies agronómicas y forestales. Con el objetivo de caracterizar los sistemas agroforestales del recinto San Francisco de la parroquia El Anegado, se realizó un inventario florístico y se recopiló información sobre el uso y manejo de los componentes de las fincas, entre febrero y marzo de 2022; se calcularon índices de diversidad de Margalef, Simpson, Shannon y la Equidad de Pielou. Entre las especies inventariadas, sobresalen, Coffea arabica L., Handroaunthus billbergii (Bureau & K. Schum.) S. O. Grose y Theobroma cacao L.; mientras que, Cedrela montana Moritz ex Turcz.; Cecropia maxima Snethl. y Handroanthus chrysanthus (Jacq.) SO Grose, están categorizadas como vulnerables. En la finca El Palmital predomina el uso alimentario (54,55 %) y en La Fortuna prevalece el maderable (51,72 %). Los índices de diversidad en ambas fincas mostraron valores altos, medios y bajos, según los índices de Margalef, Simpson y Shannon, respectivamente. El mayor uso de tierra en El Palmital es de área sembrada 74,23 % (1,80 ha) y en La Fortuna predominó la superficie no agrícola 55,88 % (0,95 ha). La caracterización de los sistemas agroforestales brinda una mejor visión de ellos, mediante la realización de inventarios de especies que reflejan la importancia, manejo y organización, permitiendo rediseñar y optimizar su funcionamiento.

Palabras clave: Inventario florístico; índices; diversidad; rediseño y fincas.

RESUMO

Os sistemas agroflorestais são uma alternativa de uso da terra e constituem uma combinação de espécies agronômicas e florestais. Com o objetivo de caracterizar os sistemas agroflorestais do recinto San Francisco da freguesia de El Anegado, foi realizado um inventário florístico e coletada informação sobre o uso e manejo dos componentes das fazendas, entre fevereiro e março de 2022. Os índices Margalef, Simpson, Shannon e Pielou Equity foram calculados. Dentre as espécies inventariadas, destacam-se Coffea arabica L., Handroaunthus billbergii (Bureau & K. Schum.) S. O. Grose e Theobroma cacao L.; enquanto, Cedrela montana Moritz ex Turcz.; Cecropia maxima Snethl. e Handroanthus chrysanthus (Jacq.) SO Grose, são classificados como vulneráveis. Na fazenda El Palmital predomina o uso alimentar (54,55 %) e em La Fortuna prevalece o uso madeireiro (51,72 %). Os índices de diversidade em ambas as fazendas apresentaram valores altos, médios e baixos, de acordo com os índices de Margalef, Simpson e Shannon, respectivamente. O maior uso da terra em El Palmital é a área plantada 74,23% (1,80 ha) e em La Fortuna a área não agrícola predominou 55,88% (0,95 ha). A caracterização dos sistemas agroflorestais proporciona uma melhor visualização dos mesmos, por meio da realização de inventários de espécies que refletem a importância, manejo e organização, permitindo redesenho e otimização de sua operação.

Palavras chave: inventário florístico; índices; diversidade; redesenhar; fazendas.

INTRODUCTION

According to the United Nations (2018), agroforestry contributes to objectives 1: end of poverty, 2: promote sustainable agriculture, objective 12: responsible production and objective and objective 15: life of terrestrial ecosystems; Therefore, through agroforestry systems, it is sought to cover the needs of people in the world with respect to the four objectives mentioned above, providing a better quality of life, production and diversification of agricultural products, agricultural sustainability and sustainable terrestrial ecosystems.

According to agroforestry systems and according to the summary version of the state of the world's forests (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO], 2022), there are three interrelated pathways based on forests and trees that can support economic and environmental recovery. These pathways are as follows: 1) stop deforestation and conserve forests; 2) restore degraded lands and expand agroforestry; and 3) using forests and creating green value chains in a sustainable way.

Agroforestry systems in the regions of Ecuador are utilization systems of great socioeconomic and biophysical relevance due to the diversification of products and services they provide (Riofrío et al., 2013). On the coast of Ecuador, it is common to find traditional agroforestry practices on farms resulting from peasant experiences. Although there is no characterization of these systems, it is possible to mention the existence of some practices used by local people. Among them are: trees in association with perennial crops, home gardens, silvopastoral practices and trees on boundaries (Aguirre et al., 2001).

The main objective of this research was to characterize the agroforestry systems of the San Francisco precinct of the El Anegado parish. All of the above based on the problem that there is a need to characterize agroforestry systems in the southern area of Manabí, as a contribution to the conservation of biological diversity at the local, regional and national level, so that small producers maintain their farms as well as their families.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Area Location

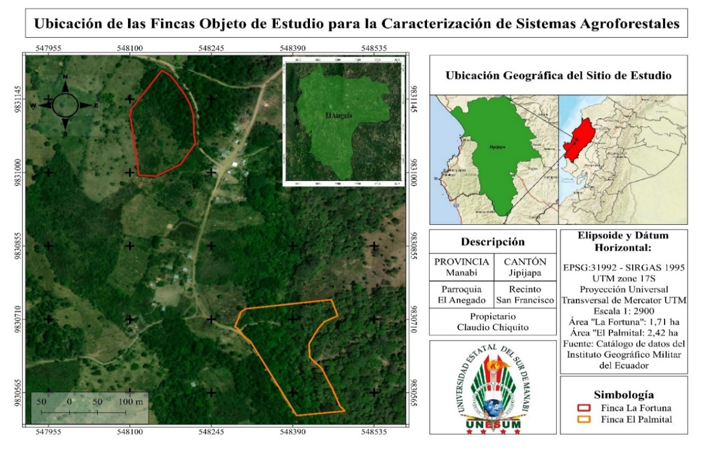

The San Francisco enclosure belongs to the El Anegado rural parish of the Jipijapa canton in the province of Manabí, covers a territorial area of 121.96 km2 and is located at kilometer 16 of the Jipijapa - Guayaquil Road, bordering to the north with the La América parish, to the south and east with the Paján canton and to the west with the Julcuy parish (GAD Parroquial de El Anegado, 2019). The work was carried out between February and March 2022 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. - Georeferencing of the San Francisco enclosure and the farms under study

Methodology

Inventory of Plant Species on the Farms Object of Study of the

San Francisco Campus of El Anegado Parish

The study included the identification of the plants present on the farms, which was resolved through inventories in order to determine diversity. Field tours were carried out, with the participation of the owner of the farms under study, the species were identified and information on their use and management was collected (Salazar et al., 2019). For the sampling, the transect method was used, according to the criteria of Mostacedo and Fredericksen, (2000) and Hernández et al. (2019) who mention that the transect method is widely used due to the speed with which it is measured and for the greater heterogeneity with which the vegetation is sampled.

Diversity Indices

The diversity indices analyzed were taken according to the criteria of Lopez et al. (2017); Jimenez et al. (2017) and Salazar et al. (2019). In addition, Microsoft Excel was used to calculate the data and later verified with the free software Past version 3.04 for Windows.

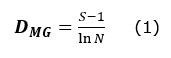

Margalef Index

This index allows to evaluate the specific richness or alpha diversity, it is evaluated from counting all the species present in the selected farms. It is mathematically evaluated from Equation 1:

Where:

S = number of species

N = total number of individuals

Simpson's Index

Known as dominance index and allows to evaluate which is the species that is found in greater proportion. According to this index, the dominant species is defined by applying Equation 2:

Where pi is the proportion of individuals in the i-th species. To calculate the appropriate shape index for a finite community, Equation 3 is used:

Where: N = Total number of individuals

For the D value, the closer the value is to one (≤ 1), the less diversity there will be in the community, otherwise when D tends to 0 there will be less dominance and greater equitability. Dominance-based indices are inverse parameters to the concept of community uniformity or evenness. Since its value is the inverse of evenness, the diversity can be calculated as 1 λ.

ShannonWiener index

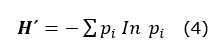

Expresses the uniformity of importance values across all species, measures structural proportional abundance. This index is based on the count of individuals in a population, assuming that all species are represented in the assessment and is calculated by applying Equation 4:

Where:

S = Number of species (species richness)

pi= Proportion of individuals of species i with respect to the total number of individuals (that

is, the relative abundance of species i), ni/N

ni= Number of individuals of species i

N = Number of all individuals of all species

The Shannon-Wiener index acquires values between zero, when there is only one species, and the logarithm of S, when all species are represented by the same number of individuals.

Equity of Pielou J´

Indicates the observed diversity in relation to the expected maximum. This index is interpreted in ranges from 0 to 1, while closer to one express that the species are equally abundant, values equal to or close to zero indicate that there is no uniformity (Jimenez et al. 2017). Equation 5 was applied to calculate Pielou's equity.

Where:

H'max = ln(S)

H' = Shannon-Wiener Index

Plant Species Threat Category inventoried

To find out the threat category of the plant species inventoried on the farms under study, the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN, 2022) was consulted, namely: EX Extinct, EW Extinct in the wild, CR Critically Endangered, EN Endangered, VU Vulnerable, NT Near Threatened, LC Least Concern, DD Data Deficient Species, NE No Data.

The scientific names of the species cited in the San Francisco enclosure were verified by reviewing the Catalog of Life (Bánki et al., 2022). On the other hand, the common names were provided by the owner of the farms.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Results of the Inventory of Plant Species on the Farms under Study

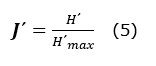

The results of the diversity inventory in the two farms showed that, in El Palmital, of all the sampled species, a large part is for food use, followed by timber use. Unlike La Fortuna, timber use predominates over food; it is worth mentioning that in both sites the lowest percentage of species was for other uses (ornamental and medicinal); the detailed information of the species with their respective use is shown in Table 1.

Within the framework of the previous observations, it is worth mentioning that, in both farms, the lowest frequency of uses was medicinal and ornamental. These results differ from the research carried out by Navarro et al. (2012), related to the diversity of useful species in agroforestry systems; These authors report seven different types of uses where the highest frequency was for firewood with 41 species, followed by medicinal with 30, utensils 29, wood 25, food 23, fodder 20 and six for live fences.

On the other hand, the results of El Palmital and La Fortuna differ from those obtained by Hernández et al. (2019), who classified the use of the species into three groups, namely: 81 % are honey, 70 % medicinal and 37 % timber. In this sense, the results obtained in the El Palmital farm are corroborated with those of Salazar et al. (2019), who reported that in the municipality of Restrepo the greatest use is for food with 51 species, followed by forestry with 38, medicinal with 27 and ornamental with 9. In the municipality of Riofrío, 34 species are used for food and five for forestry. It is worth mentioning that medicinal, fodder and ornamental uses are low in both municipalities of Valle del Cauca.

Table 1. - Distribution of agrobiodiversity inventoried on farms according to their use

Ed= Edible; Tm= Timber; Orn = Ornamental; Mdcl= Medicinal; S= Sale.

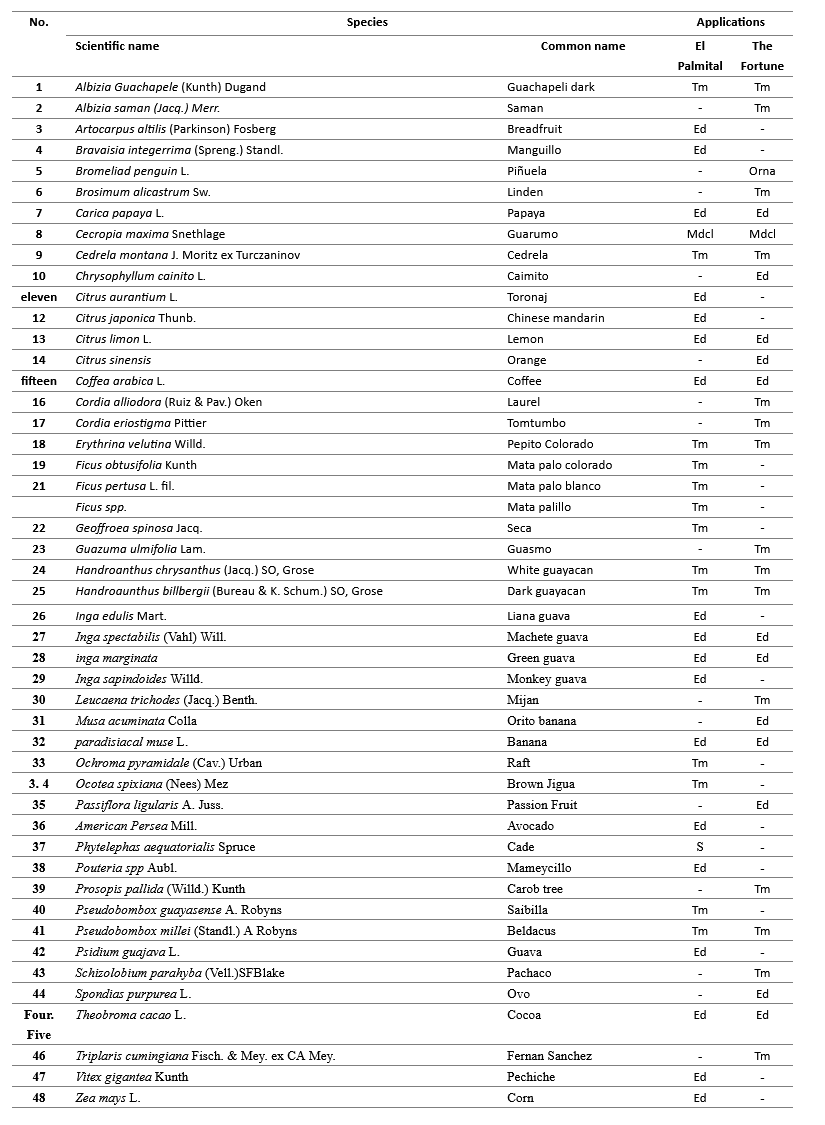

Diversity Indices

According to the values presented in Table 2, the specific richness of Margalef was higher in El Palmital, however, the values of both show a high diversity in species. Regarding the Simpson diversity index, the El Palmital farm presented a higher value indicating a high diversity, unlike the La Fortuna farm, which shows a medium diversity. The dominance values imply that these farms have a greater abundance of species and that some species are dominant.

Table 2. - Values of diversity indices, Margalef, Shannon-Weaver and Simpson of the inventories carried out on the farms under study

Equity resulted with values of 0.51 and 0.40, this indicates that there is no similarity between species and individuals evaluated since they are not close to 1, that is, in both farms, there is clear evidence of the dominance exercised by some species in the sampling areas. On the other hand, the results of the Shannon Weaver index show that both farms have values less than 2 (< 2) and this is interpreted as having a relatively low diversity of species.

When evaluating the diversity indices, it was obtained that the specific richness of Margalef in the farms under study showed a high diversity of species, this index was the one that best recorded the diversity difference. On the other hand, the Simpson index showed that in the El Palmital farm there is a high diversity, unlike La Fortuna, which shows a medium diversity.

In the same order and sense of the previous ideas, these results coincide with the studies carried out by Blanco et al. (2014), and Milián et al. (2018); who stated that the Shannon index presents a low diversity in peasant farms, in turn the high values in the richness of Margalef ratify high biodiversity of the farms under study, this demonstrates a balance between the number of species and the number of individuals present in the evaluated systems.

Regarding equity, it denoted that there is no similarity between the number of individuals and species; thus, regarding the Shannon Weaver index in both farms studied in San Francisco, the values point to a low diversity; these data coincide with the results described by Lores et al. (2008) where the farms studied by these authors show low biodiversity according to the Shannon index, because the systems are not heterogeneous enough to sustain a high specific diversity.

With reference to the above, the results obtained in the farms studied in the San Francisco enclosure differ from the values reported by Salazar et al. (2019) who determine the composition and diversity of species in two municipalities; where the Margalef, Simpson and Shannon indices show a high specific richness.

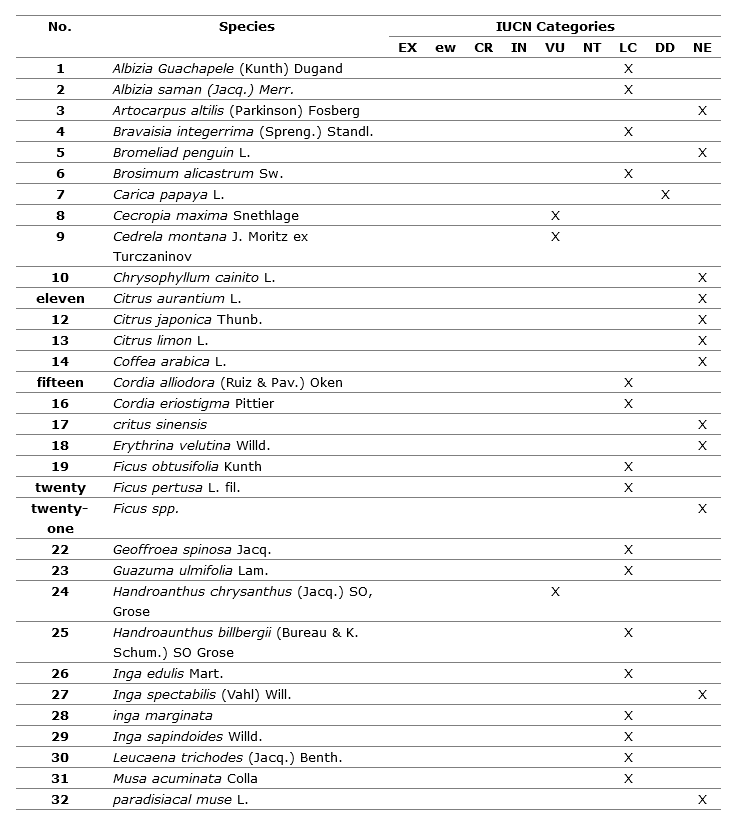

Threat Categories of Inventoried Plant Species

Based on the list of species inventoried on both farms, Table 3 was prepared, showing the threat category of each one of them.

Table 3. - Plant species categorized according to their threat category

Note. Note. EX= extinct; EW= extinct in the wild; CR= critically endangered; EN= endangered; VU= vulnerable; NT= almost threatened; LC= least concern; DD= data deficient; NE= not evaluated.

Table 4. - Continuation. Plant species categorized according to their threat category

Note. Note. EX= extinct; EW= extinct in the wild; CR= critically endangered; EN= endangered;

VU= vulnerable; NT= almost threatened; LC= least concern; DD= data deficient; NE= not evaluated.

Adapted from: Union for the Conservation of Nature (2020).

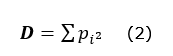

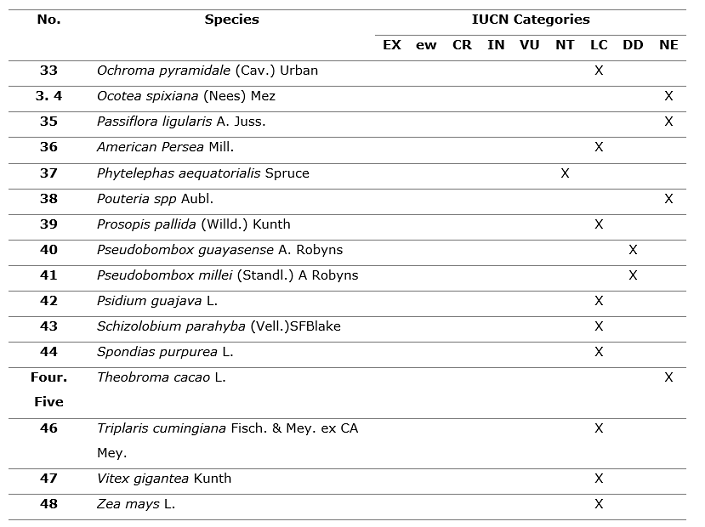

As observed in Table 4, there was a greater number of species in the category of least concern (LC), in this order of things, the species Cedrela montana J. Moritz ex Turczaninov, Cecropia maxima Snethlage and Handroanthus chrysanthus (Jacq.) SO, Grosse (Figure 2), they are reported as vulnerable (VU).

Figure 2. - Vulnerable plant species according to the IUCN threat category San

Francisco enclosure

Note. A: Cedrela montana

J. Moritz ex Turczaninov (La Fortuna farm); B:

Cecropia maxima Snethlage (La Fortuna farm); C:

Handroanthus chrysanthus (Jacq.) SO, Grose (La Fortuna farm).

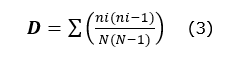

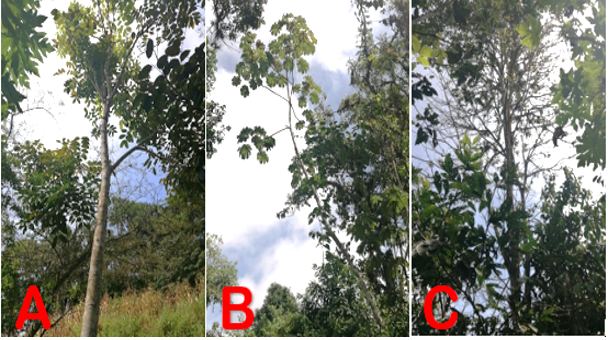

Phytelephas aequatorialis Spruce is listed as Near Threatened (NT) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. - Image of individuals of the species Phytelephas aequatorialis Spruce Finca El Palmital

It is worth mentioning that the threat species identified in the agroforestry systems of the San Francisco enclosure are generally due to their use in the timber and non-timber industry and sometimes due to agricultural expansion.

Regarding the threat category of the species Phytelephas aequatorialis, it is listed as almost threatened (NT), according to the IUCN red list (IUCN, 2022); this particular is dealt with by Jiménez et al. (2018), who explain that in 1997 the IUCN classified it as Vulnerable (VU) under criterion A. More recently, Valencia et al. (2013), place it in the Not Threatened category, however, they mention that it should be reconsidered and classified as vulnerable.

In relation to the tree species inventoried in the San Francisco enclosure, according to the IUCN red list, the species Handroanthus chrysanthus and Cedrela montana are categorized as vulnerable; this information differs from that described by Valderrama et al. (2018), where the species Handroanthus chrysanthus is categorized as Least Concern (LC). In the same way Ascencio et al. (2021) mention that the Cedrela montana species is included in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) (CITES, 2019), due to indiscriminate extraction in areas of natural distribution motivated by the qualities of its wood.

In accordance with what has been previously described, the species Cecropia maxima classified as Vulnerable (VU) coincides in the same way with the study carried out by Romero and Pitman (2003), who place it in the same category, while Berg et al. (2005) differ specifying that the genus Cecropia is not threatened.

CONCLUSION

Among the species inventoried on the El Palmital and La Fortuna farms, Coffea arabica L., Handroaunthus billbergii (Bureau & K. Schum.) S. O. Grose and Theobroma cacao L. stand out; while, Cedrela montana Moritz ex Turcz.; Cecropia maxima Snethl. and Handroanthus chrysanthus (Jacq.) SO, Grose, are categorized as vulnerable. Among the uses, the most frequent were for the El Palmital farm, food (54.55 %) and in La Fortuna timber prevails (51.72 %). In relation to the use of land in El Palmital, the planted area predominates 74.23 % (1.80 ha) and in La Fortuna the non-agricultural area 55.88 % (0.95 ha).

REFERENCES

AGUIRRE, N., HOFSTEDE, R., SEVINK, J., & ORDOÑEZ, L. 2001. Sistemas Forestales En La Costa Del Ecuador: Una propuesta para la zona de amortiguamiento de la reserva Mache-Chindul. ECOPAR. Disponible en: http://www.rncalliance.org/WebRoot/rncalliance/Shops/rncalliance/4C15/9487/9F8B/02A1 /3D0A/C0A8/D218/9663/Aguirre_et_al_2001_SFCosta2001.pdf

ASCENCIO-LINO, T., MATAMOROS-ALCÍVAR, E., SANDOYA-SÁNCHEZ, V., BARCOS-ARIAS, M., & NARANJO-MORÁN, J. 2021. An exploratory study of phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria in two habitats associated with Cedrela Montana Moritz ex Turcz. Bionatura, vol 6 no. 1, pp. 1575-1578. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.21931/RB/2021.06.01.20

BÁNKI, O., ROSKOV, Y., DÖRING, M., OWER, G., VANDEPITTE, L., HOBERN, D., REMSEN, D., SCHALK, P., DEWALT, R. E., KEPING, M., MILLER, J., ORRELL, T., AALBU, R., ADLARD, R., ADRIAENSSENS, E. M., AEDO, C., AESCHT, E., AKKARI, N., ALFENAS-ZERBINI, P., et al. 2022. Catalogue of Life Checklist (Version 2022-07-12). Catalogue of Life. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.48580/dfpz

BERG, C., FRANCO, P., & DAVIDSON, D. 2005. Cecropia. Flora Neotropica. In New York Botanical Garden Press. Vol. 94. pp. 1-230. Disponible en: http:/ /www.jstor.org/stable/4393938

BLANCO, D., SUÁREZ, J., FUNES-MONZOTE, F., BOILLAT, S., MARTÍN, G., & FONTE, L. 2014. Procedimiento integral para contribuir a la transición de fincas agropecuarias a agroenergéticas sostenibles en Cuba Integral. Pastos y Forrajes, vol 37 no. 3, pp. 284-290.Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=269133036005

CONVENCIÓN SOBRE EL COMERCIO INTERNACIONAL DE ESPECIES AMENAZADAS DE FAUNA Y FLORA SILVESTRES [CITES]. 2019. Apéndices I, II y III Convención sobre el comercio internacional de especies amenazadas de fauna y flora silvestres. UNEP. Disponible en: https://cites.org/sites/default/files/esp/app/2019/S-Appendices-2019-11-26.pdf

GOBIERNO AUTÓNOMO DESENTRALIZADO PARROQUIAL DE EL ANEGADO. 2019. Plan de Desarrollo y Ordenamiento Territorial 2019-2023. Disponible en: https://gadelanegado.gob.ec/manabi/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/PDyOT_El_Anegado_2020-1.pdf

JIMÉNEZ GONZÁLEZ, A., SALTOS ARTEAGA, E. E., RAMOS RODRÍGUEZ, M. P., CANTOS CEVALLOS, C. G., & TAPIA ZÚÑIGA, M. V. 2018. Aprovechamiento y potencialidades de uso de Phytelephas aequatorialis Spruce como producto forestal no maderable. Revista Cubana de Ciencias Forestales, vol 6 no. 3, pp. 311-326. Disponible en: http://cfores.upr.edu.cu/index.php/cfores/article/view/349

JIMÉNEZ, A., GABRIEL, J. & TAPIA, M. 2017. Ecología Forestal: Una mirada desde la UNESUM. Grupo COMPAS, Universidad Estatal del Sur de Manabí.Disponible en: http://142.93.18.15:8080/jspui/handle/123456789/181

LÓPEZ, A. S., LÓPEZ, G. G., & FAGILDE ESPINOZA, M. D. C. 2017. Propuesta de un índice de diversidad funcional. Aplicación a un bosque semideciduo micrófilo de Cuba Oriental. Bosque, vol 38 no. 3, pp. 457-466. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-92002017000300003

LORES, A., LEYVA, A., & TEJEDA, T. 2008. Evaluación Espacial Y Temporal De La Agrobiodiversidad En Los Sistemas Campesinos De La Comunidad "Zaragoza" En La Habana. Cultivos Tropicales, vol 29 no. 1, pp. 510. http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/ctr/v29n1/ctr010108.pdf

MILIÁN, I., SÁNCHEZ, S., WENCOMO, H., RAMÍREZ, W., & NAVARRO, M. 2018. Estudio de los componentes de la biodiversidad en la finca agroecológica La Paulina del municipio de Perico, Cuba. Pastos y Forrajes, vol 41 no. 1, pp. 50-55. Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/pyf/v41n1/pyf07118.pdf

MOSTACEDO, B. & FREDERICKSEN, T. 2000. Manal de métodos básicos de muestreo y análisis en ecología vegetal. Santa Cruz de la Sierra.

NACIONES UNIDAS. 2018. La Agenda 2030 y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible: una oportunidad para América Latina y el Caribe (LC/G.2681-P/Rev.3), Santiago.

NAVARRO-GARZA, H., SANTIAGO-SANTIAGO, A., MUSÁLEM-SANTIAGO, M. Á., VIBRANS-LINDEMANN, H., & PÉREZ-OLVERA, M. A. 2012. La Diversidad De Especies Útiles Y Sistemas Agroforestales. Revistas Chapingo Seria Ciencias Forestales y Del Ambiente, vol 18 no.1, pp. 71-86. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.5154/r.rchscfa.2010.11.124

ORGANIZACIÓN DE LAS NACIONES UNIDAS PARA LA AGRICULTURA Y LA ALIMENTACIÓN [FAO]. 2022. Versión resumida de El estado de los bosques del mundo 2022. Vías forestales hacia la recuperación verde y la creación de economías inclusivas, resilientes y sostenibles. Roma, FAO. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.4060/cb9363es

RIOFRÍO, J., HERRERO DE AZA, C., GRIJALVA, J., & BRAVO, F. 2013. Modelos para estimar la biomasa de especies forestales en sistemas agroforestales de la ecorregión andina del Ecuador. Congresos Forestales. Memorias VI Congreso Forestal Español, pp. 213. Disponible en: https://www.congresoforestal.es/actas/doc/6CFE/6CFE01-023.pdf

ROMERO-SALTOS, H. & PITMAN, N. 2003. Cecropia maxima. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2003: e.T43579A10807317.Disponible en: https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2003.RLTS.T43579A10807317

SALAZAR VILLARREAL, M. DEL C., VALLEJO CABRERA, F. A., & SALAZAR VILLARREAL, F. A. 2019. Inventarios e índices de diversidad agrícola en fincas campesinas de dos municipios del Valle del Cauca, Colombia. Entramado, vol 15 no. 2, pp. 264-274. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1900-38032019000200264

UNIÓN INTERNACIONAL PARA LA CONSERVACIÓN DE LA NATURALEZA [IUCN]. 2022. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2022-1. https://www.iucnredlist.org. ISSN 2307-8235. © International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

VALDERRAMA, N. T., GIL LEGUIZAMÓN, P. A., GIL NOVOA, J. E., & MORALES PUENTES, M. E. 2006. Capítulo VII Fitofenología y Estrategias Reproductivas. La vida en un fragmento de bosque en las rocas: Una muestra de diversidad andina en Bolívar, Santander (pp. 332-358). UTPC. Disponible en: https://librosaccesoabierto.uptc.edu.co/index.php/editorial-uptc/catalog/view/78/104/3420

VALENCIA, R., MONTÚFAR, R., NAVARRETE, H., & BALSLEV, H. 2013. Capítulo 13. Phytelephas aequatorialis. In Palmas Ecuatorianas: biología y uso sostenible (Primera Ed, pp. 186-201). Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259823093_Capitulo_13_Tagua_Phytelephas_aequatorialis

Conflicts of interest:

The authors declare not to have any interest conflicts.

Contribution of the authors:

Alfredo Jiménez González: Conception of the idea, search and review of the

literature, preparation of instruments, application of instruments, compilation of the

information resulting from the applied instruments, general advice on the topic addressed, writing

of the original (first version), review and final version of the article, correction of the

article, authorship coordinator, translation of terms or information obtained, review of

the application of the applied bibliographic standard.

Robert Joshua Carvajal Nunura: Conception of the idea, search and review of literature, preparation of instruments, application of instruments, compilation of the information resulting from the applied instruments, statistical analysis, preparation of tables, graphs and images, preparation of the database, writing of the original (first version), correction of the article, review of the application of the bibliographic standard applied.

Jahir Anibal Ponce Muñiz: Conception of the idea, search and review of literature, preparation of instruments, application of instruments, compilation of the information resulting from the applied instruments, statistical analysis, preparation of tables, graphs and images, preparation of the database, writing of the original (first version), correction of the article, review of the application of the applied bibliographic standard.

César Alberto Cabrera Verdesoto: Compilation of the information resulting from the applied instruments, general advice for the topic addressed, writing of the original (first version), review and final version of the article, correction of the article, authorship coordinator, translation of terms or information obtained, review of the application of the bibliographic standard applied.

Jesús de los Santos Pinargote Chóez: Compilation of the information resulting from the instruments applied, general advice on the subject matter addressed, revision and final version of the article, correction of the article, revision of the application of the bibliographic standard applied.

![]()

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0

International license.

Copyright (c) 2023 Alfredo Jiménez González, Roberth Joshua Carvajal Nunura, Jahir

Aníibal Ponce Muñiz, César Alberto Cabrera Verdesoto, Jesús De los Santos Pinargote Choez