Cuban Journal of Forest Sciences. 2023; January-April 11(1): e768.

Translated from the original in spanish

Original article

Composition, diversity and tree structure in a cloud forest above 2100 masl in Peru

Composición, diversidad y estructura arbórea en un bosque de neblina sobre 2 100 msnm en el Perú

Composição, diversidade e estrutura de árvores em uma floresta nublada acima de 2 100 m de altura no Peru

Josué Otoniel

Dilas-Jiménez1*![]() , Carlos Andrez Mugruza-Vassallo2

, Carlos Andrez Mugruza-Vassallo2![]() , José Luis Marcelo

Peña3

, José Luis Marcelo

Peña3![]()

1National Autonomous University of Tayacaja Daniel Hernández Morillo. Perú.

2National Technological University of South Lima. Perú.

3Universidad Nacional de Jaén. Perú.

*Corresponding author: jdilas@unat.edu.pe

Received:2022-08-14.

Approved:2023-03-24.

ABSTRACT

Tropical montane cloud forests in northern Peru are severely fragmented and degraded by land use change with the consequent loss of important plant biodiversity. This research had the objective of analyzing the composition, diversity and structure of the arboreal vegetation in an area of tropical montane cloud forest above 2100 m a.s.l in northern Peru. In a 1-hectare permanent plot, all trees with diametrer over 10 cm were marked and recorded. Diversity, floristic composition and structure of a relict cloud forest were analyzed. A total of 792 individuals of 81 species, 48 genera and 33 families were recorded. The most species-rich families were Lauraceae (25 species), Euphorbiaceae (five species), Melastomataceae, Clusiaceae and Rubiaceae (with 4 species each). Cyathea sp. and Miconia punctata were the most abundant and frequent species. These results show the high ecological value of the forest studied from the point of view of conservation.

Key words: Montane, cloud, diversity, floristic structure.

RESUMEN

Los bosques de neblina montanos tropicales en el norte del Perú, son severamente fragmentados y degradados por el cambio de uso de la tierra con la consecuente pérdida de importante biodiversidad vegetal. Esta investigación tuvo el objetivo de analizar la composición, diversidad y estructura de la vegetación arbórea en un área de bosque de neblina montano tropical sobre 2 100 m s.n.m en el norte del Perú. En una parcela permanente de una 1 hectárea se marcaron y registraron todos los árboles con diámetros mayores de 10 cm. Se analizó la diversidad, composición florística y estructura de un relicto de bosque neblina. Se registró un total de 792 individuos de 81 especies, 48 géneros y 33 familias. Las familias más ricas en especies fueron Lauraceae (25 especies), Euphorbiaceae (cinco especies), Melastomataceae, Clusiaceae y Rubiaceae (con 4 especies cada una). Cyathea sp1. y Miconia punctata fueron las especies más abundantes y frecuentes. Estos resultados evidencian el alto valor ecológico del bosque estudiado desde el punto de vista de la conservación.

Palabras clave: Montano, neblina, diversidad, florística, estructura.

RESUMO

As florestas tropicais montanas no norte do Peru estão severamente fragmentadas e degradadas pela mudança do uso do solo com a conseqüente perda de importante biodiversidade vegetal. Esta pesquisa teve como objetivo analisar a composição, diversidade e estrutura da vegetação arbórea em uma área de floresta tropical montana acima de 2 100 m a.s.l. no norte do Peru. Em um terreno permanente de 1 hectare, todas as árvores com diâmetro superior a 10 cm foram marcadas e registradas. A diversidade, composição florística e estrutura de uma floresta nublada foram analisadas. Um total de 792 indivíduos de 81 espécies, 48 gêneros e 33 famílias foram registrados. As famílias mais ricas em espécies foram Lauraceae (25 espécies), Euphorbiaceae (cinco espécies), Melastomataceae, Clusiaceae e Rubiaceae (com 4 espécies cada). Cyathea sp1. e Miconia punctata foram as espécies mais abundantes e freqüentes. Estes resultados mostram o alto valor ecológico da floresta estudada do ponto de vista da conservação.

Palavras-chave: Montana, floresta nublada, diversidade, florística, estrutura.

INTRODUCTION

Tropical montane cloud forests are ecosystems of high importance in the world, covering around 380,000 km2 , which represents 2.5 % of known tropical forests (Rubb et al., 2004), this importance is given by its exceptional diversity of flora that they house by demonstrating a high richness of species per area unit, being an important source of endemism, thus they also behave as efficient ecosystems in terms of ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration (Álvarez-Arteaga et al., 2013; Eller et al., 2020; Knowles et al., 2020) both in its tree biomass and mainly in the soil, being surpassed only by high Andean ecosystems (páramos-puna) with a high concentration of organic carbon (Dilas-Jiménez y Huamán Jiménez, 2020; Zimmermann et al., 2010). However, these forests are located in the most sensitive areas with climatic anomalies, unlike other terrestrial ecosystems in the world (Seddon et al., 2016) and are threatened by the effects of climate change and are mainly fragmented and degraded with change of land use (Moreira et al., 2021).

In Peru, tropical montane mist forests are located mostly from 1,000 to 3,000 masl (Van de Weg et al., 2014), in the northern Peruvian zone they are mainly located in the regions of Cajamarca, Piura and Amazonas, regions with a wide floristic diversity of around 17,000 species, 800 of these endemic (Sagástegui et al., 2003).

In the Cajamarca region, tropical montane cloud forests are located mainly in the territories of the provinces of Jaén and San Ignacio (MINAM, 2014). Since they house timber species with high demand such as Retrophyllum rospigliosii, Prumnopitys harmsiana (podocarpaceae) are suffering from selective logging, and are also threatened by high rates of deforestation in the area around 4000 hectares/year (Llerena et al., 2010). However, there is little information on ecological and hydroecological aspects provided by the tree flora in these types of forests, in general, there are very few studies carried out and published for this type of forests in northern Peru (Sagástegui et al., 2003; Seddon et al., 2016).

In Peru, studies on the diversity of the tree component are promoted, mainly in the Amazon Forest, based on sampling plots with a minimum size of one hectare (contiguous area) and standardized methodologies (Marcelo-Peña y Reynel, 2014). However, for the cloud forests in the northern zone there are very few records of published studies including one carried out by Peña y Pariente (2015) in a cloud forest in the province of San Ignacio, Cajamarca. This area is located at an altitude of 2 150 m a.s.l, 308 individuals are recorded and distributed in 31 families. There are 30 genera and 39 species, the five families with the highest importance value index being, in descending order, Podocarpaceae, Lauraceae, Rubiaceae, Melastomataceae and Clusiaceae. Likewise, Marcelo-Peña y Arroyo (2013) in a study carried out in a cloud forest in the province of Jaén, Cajamarca, over 2100 meters above sea level, recorded 2 new species for science of the Magnoliaceae family, Magnolia jaenensis, whose first collections were made with this study, and M. manguillo.

Given this, the present study had the objective of analyzing the composition, diversity and structure of the arboreal vegetation in an area of tropical montane cloud forest above 2100 masl in northern Peru.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

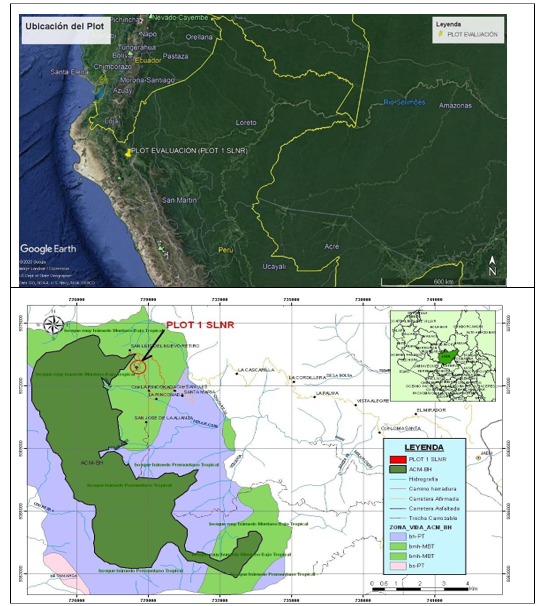

The research was carried out in a relict area of tropical montane cloud forest, at an average altitude of 2 170 m a.s.l, located in the Cajamarca region, Jaén province, Huabal district, in the San Luis del Nuevo Retiro settlement, located in the UTM coordinates 0728564 east and 9372902 north, zone 17M (Datum WGS 84). The site is located in the buffer zone of the Bosques de Huamantanga Municipal Conservation Area (ACM-BH).

The study area, following the criteria of Life Zones (Holdridge, 1978), belongs to a very humid forest-Montano Bajo Tropical (bmh-MBT), with steep slopes and undulating physiography, the temperatures range from 12º C to 17º C, and annual rainfall between 1 900 mm and 3 800 mm. The soils are characterized by being acid and abundant organic matter (IKOSlab, 2013 cited by Peña y Pariente, 2015) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. - Top: location of the permanent plot in northern Peru. Bottom: Location of the plot in the province of Jaén, Cajamarca

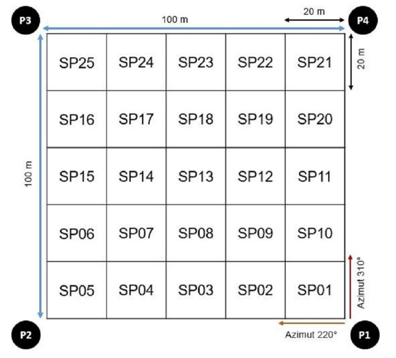

Installation of the evaluation plot

For the installation of the permanent plot, the methodology used by various authors RAINFOR, 2016; Synnott, 1979). The selection of the site for the installation was a remnant of privately owned forest in order to safeguard the conservation of the plot for future remeasurements, as well as its state of conservation in terms of existing flora. The location of the plot, the tagging and registration of trees greater than or equal to 10 cm in diameter at breast height (DBH), as well as the first botanical collections were carried out in the first half of 2008 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. - Installation and distribution of the subplots within the permanent plot

Botanical collection and record of information

The botanical collection was developed in 2 moments, the first collection was carried out in the first semester of 2008 and the second collection, in the second semester of the same year, this mainly for the samples that were collected as sterile in the first collection, in order to facilitate identification work. This work was carried out using the standard equipment, as well as the materials and procedures recommended for this type of work (Rodríguez y Rojas, 2006). For the herbalization of the collected samples, a standardized methodology was followed in these cases (Rodríguez y Rojas, 2006; Rotta et al., 2008). The collected specimens were pressed, after preservation with a solution of 60 % water and 40 % 96º alcohol, and transferred from the field to the city of Jaén, where the drying and sample mounting procedures were carried out (Marcelo-Peña et al., 2011; Rotta et al., 2008). The collected, dried and mounted specimens were sent to the MOL Herbarium of the Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina for their taxonomic identification.

Management and analysis of information

For the orderly management of data, in the field each individual registered within the permanent plot was coded with aluminum plates, for which 6-digit numerical codes were used, this being the collection code. For example, code 108220, reading from left to right, the first number indicates the Plot number (Plot 1), the next two numbers indicate the subplot number within the permanent plot (subplot 08) and finally the last three numbers indicate the number of the individual (individual 220).

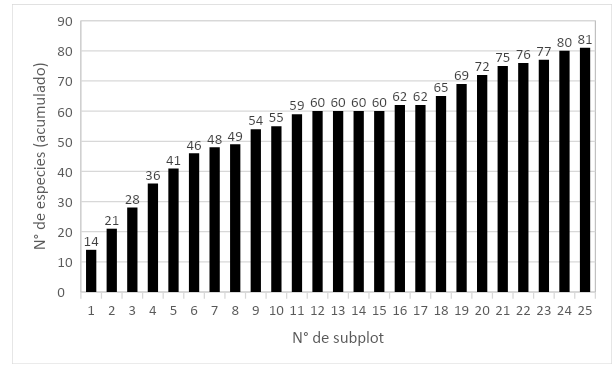

In order to know the effectiveness of the sampling, in the measurement of individuals carried out by subplot, the number of species that increased as the number of subplots analyzed was counted, with which an area-species curve graph was elaborated (Matteucci y Colma, 1982; Chu et al. 2014).

With the taxonomic identification information received from the MOL Herbarium, the following variables were analyzed (Antón y Reynel, 2004; Matteucci y Colma, 1982):

Diversity: the number of individuals per ha, number of families, number of species was determined. Likewise, the following diversity indices were determined (Equation 1); (Equation 2); (Equation 3) and (Equation 4):

Specific richness (S):

![]()

Simpson dominance index (D):

![]()

Simpson Diversity Index (1-D, Simpson, 1949):

![]()

Shannon-Wiener Equity Index (H, Hill, 1973):

![]()

Composition: the most abundant families and genera, endemic and rare species were determined.

Dasometric variables: basal area (m2) and total height (m) were determined.

Structure of the vegetation: the Density or Abundance, the Frequency and the Dominance of the identified species were calculated. With these three data, the Importance Value Index (IVI) of the total species was obtained. This index makes it possible to measure how species contribute to the structure of an ecosystem (Cottam and Curtis, 1956; Ragavan et al., 2015).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Floristic composition

A total of 792 individuals were registered for the 1ha permanent plot, belonging to 81 species of 48 genera and 33 families. The mixing quotient in this study is 0.10 (81/792), meaning that there are about 10 individuals for each species. This result is similar to those found in studies in the central jungle of Peru (Marcelo-Peña and Reynel, 2014), but lower than other studies carried out in previous years in these same areas where the mixing ratios were around 0.22 (Antón and Reynel, 2004). The low mixing coefficient found would be linked to the high proportion of individuals of two Cyathea sp. and Miconia punctata that represented 48 % of the total.

In the analysis of the area-species curve, of the total species registered (81), it was found that 67 % of these were completed in subplot 9 and 85 % when completing subplot 19 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. - Area-species curve in the evaluated permanent plot

Floristic diversity

The Lauraceae family (25 species) is the richest in species, followed by Euphorbiaceae (five species), Melastomataceae , Clusiaceae and Rubiaceae (with four species each). The Lauraceae family is endemic to these montane forests in Peru, with greater abundance in its genera Ocotea and Nectandra (León, 2006), as well as an important presence of the Melastomataceae family in its genus Miconia (Ledo et al., 2012) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. - Relative abundance of species by family in the montane cloud forest, Jaén, Cajamarca

In an evaluation carried out in the forests of Chinchiquilla, San Ignacio, montane cloud forest at 2150 masl, similar results were found in terms of the five families with the largest number of individuals such as Melastomataceae and Rubiaceae, and the mixture quotient found in this investigation. Nevertheless, a striking difference is evident because in these forests of San Ignacio the podocarp species or trees known in the area as "romerillos" stand out in number (Peña and Pariente, 2015).

Regarding the alpha diversity according to the indices analyzed, where a population would be homogeneous if the spatial distribution between species is uniform in the study area ( Matteucci and Colma, 1982), the results for the present study are: Specific richness (S), with a value of 81 species; Simpson dominance index (D), with a value of 0.138; Simpson diversity index (1-D), with a value of 0.862; and the Shannon-Wiener (H) Equity Index, with a value of 2.856. Thus, considering the Shannon Index as an indicator of homogeneity of an evaluated ecosystem (Shi and Zhu, 2009), the forest evaluated in the present study showed intermediate values, similar to those found in a permanent plot installed in the same area over 2 500 m a.s.l, (Pérez, 2011), as well as similar to evaluation results in Fundo Génova, Chanchamayo, in late secondary forest type (Antón and Reynel, 2004), but lower than the values of this index (3.309) found for the forest a montane cloud forest in Chinchiquilla, San Ignacio, Cajamarca (Peña and Pariente, 2015) and lower than results from other premontane and montane forests in La Merced, San Ramón and Satipo in Peru (Marcelo-Peña and Reynel, 2014).

Endemism

When comparing the list of species with the Catalog of Angiosperms and Gymnosperms of Peru (Brako and Zarucchi, 1993), six endemic species were recorded:

It should be noted that individuals of Podocarpus oleifolius (Podocarpaceae ), which is the only coniferous family native to Peru and which is typical of the cloud forests in the provinces of Jaén and San Ignacio in Cajamarca, in a permanent plot installed in the forests of Chinchiquilla in San Ignacio it was found that these Podocarpaceae ( Prumnopitys harmsiana and podocarpus glomeratus ) represent 12% of the total number of individuals (Peña y Pariente, 2015). These podocarps are protected in the Tabaconas Namballe National Sanctuary (TNNS) but are highly threatened by indiscriminate logging because they are a highly required timber species in the area (Elliot, 2009; Llerena et al., 2010).

Likewise, the presence of an individual that in this study was preliminarily identified as a species of the genus Talauma (Magnoliaceae), known as "military. This was the basis for subsequent studies in the area, mainly around the town of San Luis del Nuevo Retiro, where the existence of Magnoliaceae species new to science was effectively confirmed, thus reporting two new species named Magnolia jaenensis and M. manguillo. These new species correspond to the first records of Magnolia in montane forests above 2 100 m a.s.l (Marcelo-Peña and Arroyo, 2013).

It is not ruled out that there could be other endemic or new species for the Peruvian flora and even for science; because several of the collected specimens were recorded without reproductive organs (flowers and/or fruits), making it difficult to identify the taxonomic specimens up to the species level.

Vegetation structure (abundance, frequency and dominance)

Of the 792 individuals registered, the five most abundant species, which represent 63 % of the total number of individuals, are Cyathea sp. (30.93 %), Miconia punctata (17.17 %), Helicostylis tovarensis (6.69 %), Myrcia sp. (4.80 %) and Hedyosmum angustifolium (3.66 %), see details in appendix 1.

The five most abundant genera in descending order are Cyathea (Pteridophyta) with 245 individuals (30.93 %), Miconia (Melastomataceae) with 140 individuals (17.68 %), Helicostylis (Moraceae) with 53 individuals (6.69 %), Myrcia (Myrtaceae) with 42 individuals (5.30 %) and Ocotea (Lauraceae) with 32 individuals (4.04 %).

Likewise, the five most abundant in order are Cyatheaceae (31.31 %), Melastomataceae (18.31 %), Lauraceae (7.58 %), Moraceae (7.20 %) and Myrtaceae (5.30 %). Cyatheaceae was the most abundant family in the studied site. These families are typical of these types of montane forests in America (Ledo et al., 2012; Schin-ichiro and Kitayama, 1999), even some of these are also present on other continents (Shi and Zhu, 2009).

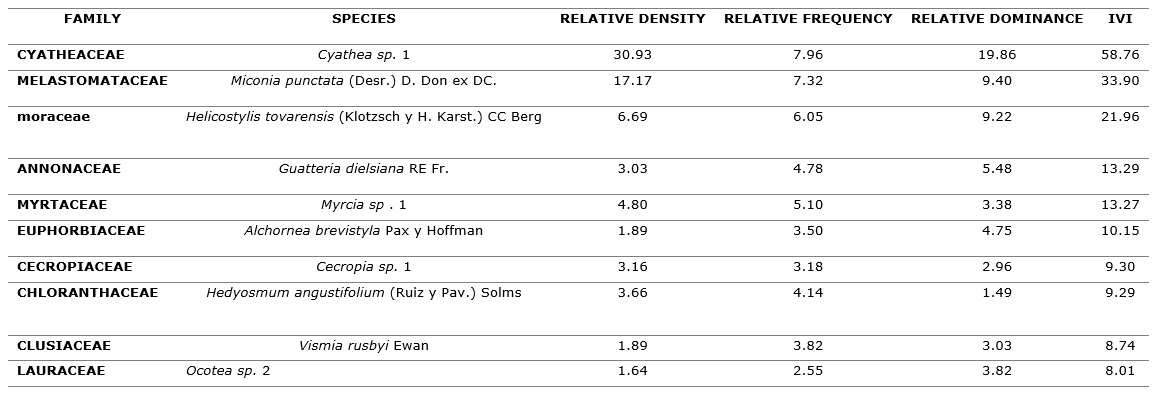

Regarding the frequency and dominance, these variables are closely related to the abundance of the species. Table 1 shows the Importance Value Index (IVI) for the ten most important species (see details in Appendix 1), where it can be seen that only two Cyathea sp. and Miconia punctata represent close to a third of the total IV (Table 1).

Table 1. - Importance Value Index of the ten most important species of the forest studied

The notable abundance of Cyatheaceae in the studied forest is due to the fact that this family is representative of montane forests, at least 83 species of the genus Cyathea are recognized in Peru (Lehnert, 2011).

These results are also similar to the other studies outcomes in analogous ecosystems in the Central Peruvian Forest where there was found a dominance of genus Miconia of Melastomataceae (Lehnert, 2011), although in this study it is one of the most abundant families, it is much less diverse than the Lauraceae (Figure 4).

According to the analysis of Density, Frequency and Dominance of all species found in the permanent plot, the Importance Value Index (IVI) found for the first five species, in decreasing order is: Cyathea sp 1 (58.76), Miconia punctata (33.90), Helicostylis tovarensis (21.96), Guatteria dielsiana (13.29) and Myrcia sp. (13.27).

These results differ in terms of their level of importance for the first 5 species found in the montane cloud forests in the area of San Ignacio, Cajamarca, where the Prumnopitys species harmsiana and Podocarpus glomeratus (podocarp) are the most important, followed by Cinchona sp., Cecropia sp. and Endlicheria sp. (Peña y Pariente, 2015). Species of the genus Miconia (Melastomataceae ), species of the genus Guatteria (Annonaceae) and species of Moraceae are reported among the first 10 species of importance in montane and premontane forests in Peru (Antón and Reynel, 2004; Marcelo-Peña y Reynel, 2014; Peña and Pariente, 2015). In Appendix 1, the Importance Value Index (IVI) of all the species is shown.

Dasometric and volumetric variables of the species

Of all the individuals registered within the census, the average diameter (DBH) was 19.64 cm, with a variance of 90.5; the total basal area is 29.62 m2, the average basal area per individual is 0.037 m2, with a variance of 0.002; the total height of the trees has an average of 10.53m, with a variance of 13.86; and the commercial height has an average of 6.72 m, with a variance of 5.19. In an evaluation carried out in the same forested area but at an altitude of 2 543 m a.s.l, an average DBH of 16.44 cm was found (Pérez, 2011), which indicates that at higher altitudes the diameters of the trees reduce. While in another forest of fog in San Ignacio, Cajamarca whose permanent plot was installed at a height similar to the present study, an average DAP of 25.20 cm was found, this greater diameter was influenced by the high presence of individuals of the Podocarpaceae family that have the highest height and diameters, since they correspond to timber forest species in the area (Peña and Pariente, 2015).

CONCLUSIONS

The tropical montane cloud forests located in the upper zone of the province of Jaén have an important diversity of species, as well as endemic species and the potential to host species new to science.

Lauraceae family, with 15 recorded species, was the most diverse family in the studied forest, thus confirming that the Lauraceae are one of the most diverse families in the montane forests of Peru.

Regarding the vegetal structure of the studied forest, the high abundance of the Cyatheaceae family and, as well as the Melastomataceae family, confirms the representativeness of species of these families in montane cloud forests.

REFERENCES

ÁLVAREZ-ARTEAGA, G., CALDERÓN, N. E. G., KRASILNIKOV, P., Y GARCÍA-OLIVA, F. 2013. Almacenes de carbono en bosques montanos de niebla de la Sierra Norte de Oaxaca, México. Agrociencia, vol. 47 no. 2, pp. 171-180. Disponible en: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?pid=S1405-31952013000200006yscript=sci_abstractytlng=pt

ANTÓN, D., Y REYNEL, C. 2004. Relictos de bosques de excepcional diversidad en los Andes Centrales del Perú (UNALM (ed.); Primera Ed). APRODES/Asociación Peruana para la Promoción del Desarrollo Sostenible. Disponible en: http://infobosques.com/descargas/biblioteca/446.pdf

BRAKO, L., Y ZARUCCHI, J. L. 1993. Catalogue of the flowering plants and gymnosperms of Peru: Catálogo de las angiospermas y gimnospermas del Perú. Monographs in Systematic Botany from the Missouri Botanical Garden, 45, 11286.

CHU, C., SMITH, W. y SOLOW, A. 2014. A hidden species-area curve. Environ Ecol Stat 21, pp. 113-124. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10651-013-0247-2

COTTAM, G., Y CURTIS, J. T. 1956. The Use of Distance Measures in Phytosociological Sampling. Ecology, vol. 37 no. 3, pp. 451-460. DOI. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1930167

DILAS-JIMÉNEZ, J. O., Y HUAMÁN JIMÉNEZ, A. O. 2020. Captura de carbono por un bosque montano de neblina del Perú. Revista de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica Alpha Centauri, vol. 1 no. 3, pp. 13-25. DOI. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.47422/ac.v1i3.16

ELLER, C. B., MEIRELES, L. D., SITCH, S., BURGESS, S. S. O., Y OLIVEIRA, R. S. 2020. How Climate Shapes the Functioning of Tropical Montane Cloud Forests. Current Forestry Reports, vol. 6 no. 2, pp. 97-114. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40725-020-00115-6

ELLIOT, J. 2009. Los bosques de la cuenca transfronteriza del rio Mayo-Chinchipe Perú-Ecuador (ITDG (ed.); Primera Ed). Soluciones Prácticas ITDG. Disponible en: http://infobosques.com/portal/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Los-bosques-de-la-cuenca-transfronteriza-del-río-Mayo-Chinchipe.pdf

Hil, H.l 1973. Diversity and Evenness: A Unifying Notation and Its Consequences. Ecology, vol. 54 no. 2, pp. 427-432. Doi:10.2307/1934352

HOLDRIDGE, L. R. 1978. Ecología basada en zonas de vida. IICA, Instituto Interamericano de Ciencias Agrícolas 1978 - 216 pp. Disponible en:.https://books.google.com.cu/books?id=Sg1oK3Zhn10C&printsec=copyright#v=onepage&q&f=false

KNOWLES, J. F., SCOTT, R. L., BIEDERMAN, J. A., BLANKEN, P. D., BURNS, S. P., DORE, S., KOLB, T. E., LITVAK, M. E., Y BARRON-GAFFORD, G. A. 2020. Montane forest productivity across a semiarid climatic gradient. Global Change Biology, August, pp. 114. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15335

LEDO, A., CONDÉS, S., Y ALBERDI, I. 2012. Forest biodiversity assessment in Peruvian Andean Montane cloud forest. Journal of Mountain Science, vol. 9 no. 3, pp. 372-384. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-009-2172-2

LEHNERT, M. 2011. The Cyatheaceae (Polypodiopsida) of Peru. Brittonia, vol. 63 no. 1, pp. 11-45. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12228-009-9112-x

LEÓN, B. 2006. Lauraceae endémicas del Perú. Revista Peruana de Biología, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 669-677. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?script=sci_arttextypid=S1727-99332006000200065

LLERENA, C., CRUZ-BURGA, Z., DURT, É., MARCELO-PEÑA, J., MARTINEZ, K., Y OCAÑA, J. 2010. Gestión ambiental de un ecosistema frágil. Los bosques nublados de San Ignacio, Cajamarca, cuenca del rio Chinchipe (ITDG (ed.); Primera Ed). Soluciones Prácticas ITDG. Disponible en: http://infobosques.com/portal/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Gestión-ambiental-de-un-ecosistema-frágil.pdf

MARCELO-PEÑA, J.L., Y ARROYO, F. 2013. Magnolia jaenensis y M. manguillo, nuevas especies de Magnoliaceae del norte de Perú. Brittonia, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 106-112. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12228-012-9280-y

MARCELO-PEÑA, J.L., Y REYNEL, C. 2014. Patrones de diversidad y composición florística de parcelas de evaluación permanente en la selva central de Perú. Rodriguesia, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 35-47. Disponible en: http://rodriguesia-seer.jbrj.gov.br/index.php/rodriguesia/article/view/735

MARCELO-PEÑA, JOSÉ L., REYNEL RODRÍGUEZ, C., Y ZEVALLOS, P. (2011). Manual de Dendrología. CONCYTECEditor: JL Marcelo Peña ISBN: 978-9972-50-131-9. Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266560129_Manual_de_Dendrologia

MATTEUCCI, S., Y COLMA, A. 1982. Metodología para el estudio de la vegetación. Secretaría General de la Organización de los Estados Americanos. Disponible en: https://aulavirtual.agro.unlp.edu.ar/pluginfile.php/76505/mod_resource/content/3/MatteucciColma1982.pdf

MINAM. 2014. Perú reino de bosques (P. Editores (ed.); Primera Ed). Ministerio del Ambiente. Disponible en: http://www.bosques.gob.pe/archivo/1455ad_perureinodebosques.pdf

MOREIRA, B., VILLA, P. M., ALVEZ-VALLES, C. M., Y CARVALHO, F. A. 2021. Species composition and diversity of woody communities along an elevational gradient in tropical Dwarf Cloud Forest. Journal of Mountain Science, vol 18, no. 6, pp. 1489-1503. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-020-6055-x

PEÑA, G., Y PARIENTE, E. 2015. Composición y diversidad arbórea en un área de bosque de Chinchiquilla, San Ignacio-Cajamarca, Perú. Arnaldoa, vol 22, no 1, pp. 139-154. Disponible en: http://200.62.226.189/Arnaldoa/article/viewFile/187/175

RAGAVAN, P., SAXENA, A., MOHAN, P. M., RAVICHANDRAN, K., JAYARAJ, R. S. C., Y SARAVANAN, S. 2015. Diversity, distribution and vegetative structure of mangroves of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. Journal of Coastal Conservation, vol 19, no. 4, pp. 417-443. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-015-0398-4

RAINFOR. 2016. Manual de Campo para el Establecimiento y Remedición de Parcelas. Disponible en: http://www.rainfor.org/upload/ManualsSpanish/Manual/RAINFOR_field_manual_version2016_ES.pdf

RODRÍGUEZ R., E. F., Y ROJAS G., R. P. 2006. El herbario. Administración y manejo de colecciones botánicas. ISSUU. Disponible en: https://issuu.com/ericrodriguezr/docs/herbario

ROTTA, E., DE CARVALHO, L. C., Y ZONTA, M. 2008. Manual de Prática de Coleta e Herborização de Material Botânico (EMBRAPA (ed.); 1a edição). Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) Embrapa Florestas. Disponible en: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/handle/doc/315636

RUBB, P., MAY, L., MILES, L., Y SAYER, J. 2004. Cloud forest agenda (UNEP (ed.); First Edit). United Nations Environment Programme-UNEP. Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318657347_Cloud_Forest_Agenda

SAGÁSTEGUI, A., SÁNCHEZ, I., ZAPATA, M., Y DILLON, M. 2003. Diversidad florística del norte del Perú, Tomo II bosques montanos (GRAFICART (ed.). GRAFICART. Disponible en: https://www.nhbs.com/diversidad-floristica-del-norte-de-peru-volume-2-book

SCHIN-ICHIRO, A., Y KITAYAMA, K. 1999. Structure, Composition and Species Diversity in an Altitude-Substrate Matrix of Rain Forest Tree Communities on Mount Kinabalu, Borneo Author (s): Shin-ichiro Aiba and Kanehiro Kitayama Structure, mat. Plant Ecology, vol, 140, no 2, pp. 139-157. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20050735 DOI. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009710618040

SEDDON, A. W. R., MACIAS-FAURIA, M., LONG, P. R., BENZ, D., Y WILLIS, K. J. 2016. Sensitivity of global terrestrial ecosystems to climate variability. Nature, 531, pp. 65-72. Disponible en: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16986

SHI, J. P., Y ZHU, H. 2009. Tree species composition and diversity of tropical mountain cloud forest in the Yunnan, southwestern China. Ecological Research, vol 24, no 1, pp. 83-92. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11284-008-0484-2

SIMPSON, E. .1949. Measurement of diversity. Nature 163688. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1038/163688a0

SYNNOTT, T. J. 1979. Manual of permanent plot procedures for tropical rainforests. Tropical Forestry Papers. Oxford University. Disponible en: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:c1ab9dff-f60a-4d9b-9b3d-5706264b1d4d/download_file?file_format=pdfysafe_filename=TFP14.pdfytype_of_work=Working+paper

VAN DE WEG, M. J., MEIR, P., WILLIAMS, M., GIRARDIN, C., MALHI, Y., SILVA-ESPEJO, J., Y GRACE, J. 2014. Gross Primary Productivity of a High Elevation Tropical Montane Cloud Forest. Ecosystems, vol, 17, no 5, pp. 751-764. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-014-9758-4

ZIMMERMANN, M., MEIR, P., SILMAN, M. R., FEDDERS, A., GIBBON, A., MALHI, Y., URREGO, D. H., BUSH, M. B., FEELEY, K. J., GARCIA, K. C., DARGIE, G. C., FARFAN, W. R., GOETZ, B. P., JOHNSON, W. T., KLINE, K. M., MODI, A. T., RURAU, N. M. Q., STAUDT, B. T., Y ZAMORA, F. 2010. No differences in soil carbon stocks across the tree line in the Peruvian Andes. Ecosystems, vol 13 no. 1, pp. 62-74. DOI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-009-9300-2

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors' contribution:

The authors have participated in the writing of the work and analysis of the documents.

![]()

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0

International license.

Copyright (c) 2023

Josué Otoniel

Dilas-Jiménez, Carlos Andrez Mugruza-Vassallo, José Luis Marcelo

Peña