Cuban Journal of Forest Sciences. 2021; January-Arpril 9(1): 1-16

Translated from the original in spanish

Floristic composition, structure and endemism of the woody component of the Huashapamba forest, Loja, Ecuador

Composición florística, estructura y endemismo del componente leñoso del bosque Huashapamba, Loja, Ecuador

Composição florística, estrutura e endemismo da componente lenhosa da floresta de Huashapamba, Loja, Equador

Zhofre Huberto Aguirre Mendoza1*![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6829-3028

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6829-3028

Leidy Cango Sarango2 ![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8477-7623

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8477-7623

Wilson Quizhpe Coronel3 ![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4726-9125

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4726-9125

1National University of Loja. Ecuador.

2Private Consultant.

Ecuador.

3Amazon State University.

Ecuador.

*Correspondence author: zhofre.aguirre@unl.edu.ec

Received:28/09/2020.

Approved:11/11/2020.

ABSTRACT

Andean forests are diverse and highly valued ecosystems, it is necessary to characterize their resources for their management. For this purpose, a permanent plot was studied in the Andean forest of Huashapamba, with the objective of determining the composition, structure and endemism of the woody component. A permanent plot of 1 hectare was installed, which was divided into 25 subplots of 400 m²; the diameter (1.30) and height of all individuals ≥ 5 cm were recorded. Floristic composition, endemism, Shannon index, density, abundance, frequency, dominance and importance value index were determined; basal area, volume per species and diameter structure were also calculated. Fifty-four species were recorded within 39 genera, 27 families and six endemic species. The basal area was 30.24 m2 ha-1 and volume was 215.86 m3 ha-1. According to the Shannon index, diversity is medium (3.10). The species with the highest density are Cyathea caracasana, Hedyosmun scabrum and Verbesina lloensis, which are also the most abundant. Cyathea caracasana, Hedyosmun scabrum and Solanum goniocaulon are the most frequent species in the forest; and, Cyathea caracasana, Clethra revoluta and Schefflera acuminata are dominant species. The species with the highest IVI are: Cyathea caracasana, Clethra revoluta and Hedyosmun scabrum. The diameter classes reflect an inverted "J" characteristic of recovering forests. The vertical structure shows three strata: dominant, co-dominant and dominated. The Andean forest remnant studied is a representative sample of floristic diversity of this type of forest, which justifies its conservation under some management category.

Keywords: Diversity; Montane forest; Huashapamba; Conservation; Endemism; Saraguro.

RESUMEN

Los bosques andinos son ecosistemas diversos y muy preciados, es necesario caracterizar sus recursos para su manejo. Para esto, se estudió una parcela permanente en el bosque andino de Huashapamba, con el objetivo de determinar la composición, estructura y endemismo del componente leñoso. Se instaló una parcela permanente de 1 hectárea, que fue dividida en 25 subparcelas de 400 m²; se registró el diámetro (1,30) y altura de todos los individuos ≥ 5 cm. Se determinó la composición florística, endemismo, índice de Shannon, densidad, abundancia, frecuencia dominancia e índice de valor de importancia; también se calculó el área basal, volumen por especie y estructura diamétrica. Se registraron 54 especies dentro de 39 géneros, 27 familias y seis especies endémicas. El área basal fue de 30,24 m2 ha-1 y volumen de 215,86 m3 ha-1. Según el índice de Shannon, la diversidad es media (3,10). Las especies con mayor densidad son Cyathea caracasana, Hedyosmun scabrum y Verbesina lloensis, que también son las más abundantes. Cyathea caracasana, Hedyosmun scabrum y Solanum goniocaulon son las especies más frecuentes del bosque; y, Cyathea caracasana, Clethra revoluta y Schefflera acuminata son especies dominantes. Las especies con IVI más alto son: Cyathea caracasana, Clethra revoluta y Hedyosmun scabrum. Las clases diamétricas reflejan una "J" invertida característica de bosques en recuperación. En el perfil vertical, se observa tres estratos: dominantes, codominantes y dominados. El remanente de bosque andino estudiado es una muestra representativa de diversidad florística de este tipo de bosque, que justifica su conservación bajo alguna categoría de manejo.

Palabras clave: Diversidad; Bosque montano; Huashapamba; Conservación; Endemismo, Saraguro.

RESUMO

As florestas andinas são ecossistemas diversos e altamente valorizados, é necessário caracterizar os seus recursos para a sua gestão. Para este efeito, foi estudada uma parcela permanente na floresta andina de Huashapamba, com o objetivo de determinar a composição, a estrutura e o endemismo da componente lenhosa. Foi instalada uma parcela permanente de 1 hectare, que foi dividida em 25 subquadrantes de 400 m²; o diâmetro (1,30) e a altura de todos os indivíduos ≥ 5 cm foram registados. Composição florística, endemismo, índice de Shannon, densidade, abundância, frequência, dominância e índice de valor de importância foram determinados; área basal, volume por espécie e estrutura de diâmetro foram também calculados. Cinquenta e quatro espécies foram registadas dentro de 39 géneros, 27 famílias e seis espécies endémicas. A área basal era de 30,24 m2 ha-1 e o volume era de 215,86 m3 ha-1. De acordo com o índice de Shannon, a diversidade é média (3,10). As espécies com maior densidade são Cyathea caracasana, Hedyosmun scabrum e Verbesina lloensis, que são também as mais abundantes. Cyathea caracasana, Hedyosmun scabrum e Solanum goniocaulon são as espécies mais frequentes na floresta; e, Cyathea caracasana, Clethra revoluta e Schefflera acuminata são as espécies dominantes. As espécies com a IVI mais elevada são: Cyathea caracasana, Clethra revoluta e Hedyosmun scabrum. As classes de diâmetro refletem um "J" invertido característico da recuperação das florestas. No perfil vertical, são observados três estratos: dominante, codominante e dominado. O remanescente florestal andino estudado é uma amostra representativa da diversidade florística deste tipo de floresta, o que justifica a sua conservação sob alguma categoria de gestão.

Palavras chave: Diversidade; Floresta montana; Huashapamba; Conservação; Endemismo, Saraguro.

INTRODUCTION

Neotropical forests are the most diverse in the world in terms of species richness, and much of this is concentrated in the Andean forests, considered the global epicenter of biodiversity (Meyers 1990; Gentry 1982; 1995). There are 31 million hectares of forests distributed in the Andes of Peru, Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela, Chile and Argentina. In Ecuador there are 12 631 198 ha of forest and approximately 1 353 671.91 are Andean forest (MAE 2017) and, much of the diversity is located in the Andean region, with 4 537 species of vascular plants (Jorgensen and León 1999).

Andean forests are located in areas with steep environmental gradients associated with the complex topography of the Andes. They are considered fragile ecosystems and vulnerable to the combined effects of climate change, deforestation and degradation (MAE 2017). At the same time, they have the potential to contribute to climate change mitigation, restore ecosystem functions and provide environmental goods and services (Herzog et al., 2012).

These ecosystems are threatened, especially in southern Ecuador. The high level of vulnerability of these ecosystems to climate change requires actions for their conservation, not only because of their biological richness, but also because of the amount of non-timber forest products that people harvest and because of their fundamental role in the provision of ecosystem services: scenic beauty, biodiversity, CO2 capture, and especially the regulation and maintenance of water. Currently only 5 to 10 % of its original extension remains. (Cuesta et al., 2009; Brown and Kappelle 2001; Peralvo et al., 2013).

Studies in Andean ecosystems of southern Ecuador show the important and high floristic diversity of these ecosystems, as well as the difference in flora, apparently due to the influence of the Huancabamba geological depression. In addition, they show their problems, the fragmentation, the area that currently remains and the few studies conducted (Yaguana et al., 2012; Aguirre et al., 2017; Aguirre et al., 2018).

In the western part of the Saraguro canton, is located the forest remnant of Huashapamba, owned by several indigenous communities of the Saraguro people, this ecosystem is a space for research on flora and fauna, and can become a reference for scientific information and tourist attraction (GAD Saraguro et al., 2008).

In this context, the research was carried out to determine the floristic composition, structure and endemism of the woody component of the Huashapamba Andean forest, data that will serve as a baseline for studies of forest dynamics and sustainable management of this fragile ecosystem.

MATERIALES Y MÉTODOS

Study area

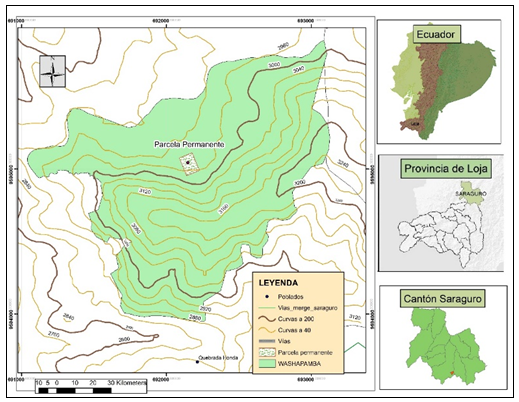

The study area is located in the Tenta parish, Saraguro canton, Loja province, Ecuador. It is owned by three indigenous communities: Lagunas, Ilincho and Gunudel. The Huashapamba forest is located 5 km from the Saraguro cantonal capital (Figure 1). It covers an area of 217.42 ha, at an altitudinal range of 2,800 to 3,000 m a.s.l., between UTM coordinates: X = 9595044, Y = 692148 (GAD Saraguro et al., 2008).

Figure 1. - Map showing the location of the Huashapamba forest area in the national and provincial context

Sampling unit

A permanent plot of 100 x 100 m (10 000 m2) was set up and subdivided into 25 plots of 400 m² (20 x 20 m); the vertexes of the plots were marked with milestones of cement and PVC pipes. In each subplot, all individuals with a diameter ≥ 5 cm at 1.30 m from the ground were measured and recorded. Each individual was identified with aluminum plates with an alphabetical-numerical code placed at 1.45 m from the ground. The total height was measured with a Sunnto hypsometer. The marking, recording and collection of the woody individuals followed the methodology of Phillips et al., (2016) and Aguirre (2019).

Botanical samples of all individuals were collected and identified in the LOJA herbarium of the Universidad Nacional de Loja, where they were deposited. The nomenclature of the scientific names follows the APG IV system.

Calculations and data analysis of the woody component of the forest

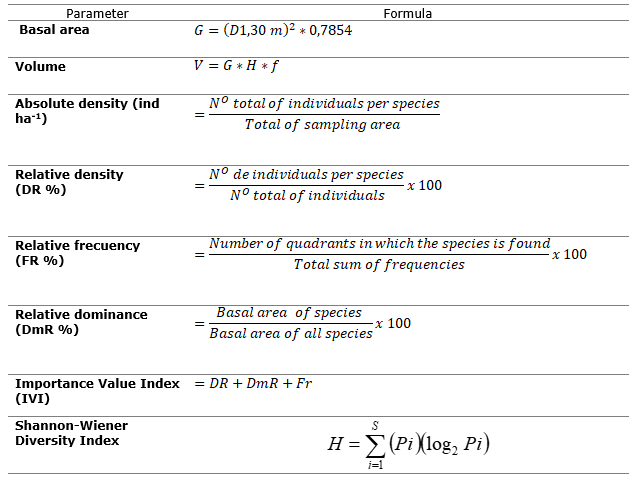

The dasometric and structural parameters of the vegetation and the Shannon-Wiener diversity index were determined, applying the formulas proposed by Moreno (2001) (Table 1).

Table 1. - Parameters and formulas used for the analysis of data from the permanent plot of the Huashapamba forest, Saraguro, Loja

Endemism

To determine the endemism and conservation status of the species, the red book of endemic species of Ecuador (León et al., 2011) and the red list of threatened species of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) were reviewed.

RESULTS

Floristic diversity of the Huashapamba forest

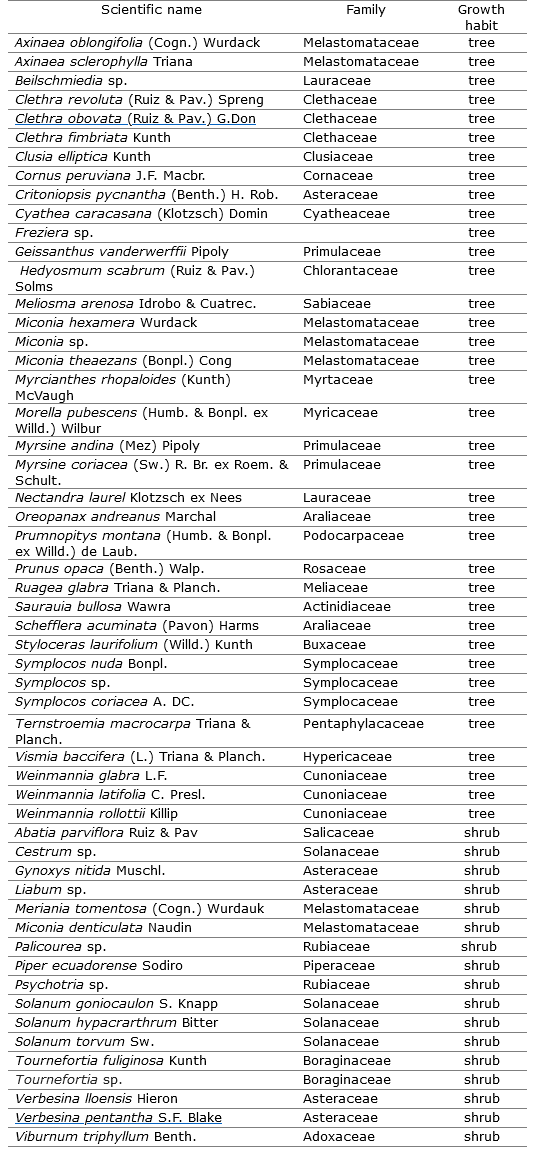

Fifty-four species, 39 genera and 27 families were recorded. According to life forms 37 are trees and 17 are shrubs (Table 2). The most diverse families were Melastomataceae (7 species), Asteraceae (5), Solanaceae (4). The Shannon index was 3.10 which is interpreted as average diversity according to the homogeneity of the samples and individuals sampled.

Table 2. - Trees and shrubs present in the permanent plot of the Huashapamba forest

Endemism of the woody component of the Huashapamba forest

Six endemic species were recorded: Oreopanax andreanus (category of less concern); Verbesina pentantha and Geissanthus vanderwerffii (threatened); Miconia hexamera, Axinaea sclerophylla (vulnerable) and Prumnopitys montana have shared endemism in South American countries.

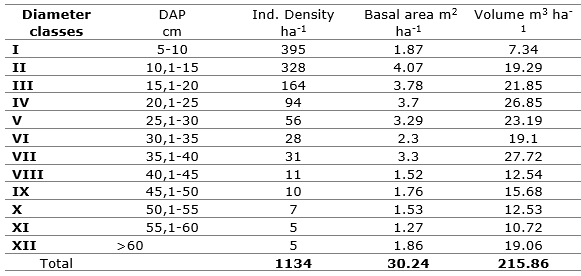

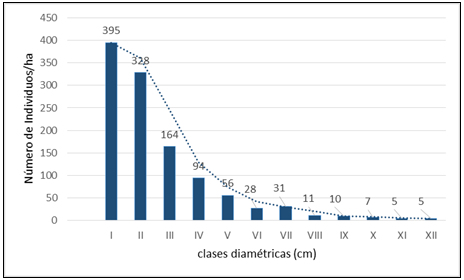

Diametric structure of the Huashapamba forest

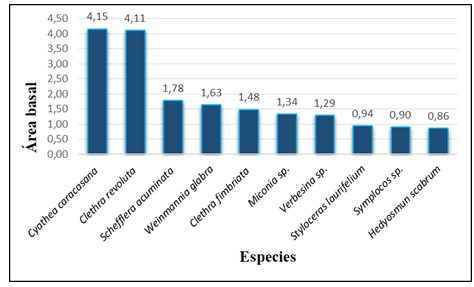

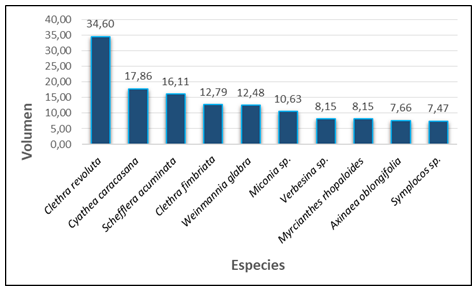

The woody component has a basal area of 30.24 m² ha-1 and a volume of 215.86 m3 ha-1 (Table 3). The species with the largest basal area were Cyathea caracasana, Clethra revoluta and Schefflera acuminata (Figure 2). The species with the greatest volume were Clethra revoluta, Cyathea caracasana and Schefflera acuminata (Figure 3). Three tree strata are observed: dominant, co-dominant and dominated.

Table 3. - Diameter classes of the woody component of the species recorded in the Huashapamba forest, Loja, Ecuador

Figure 2. - Species with the largest basal area in the woody component of the Huashapamba forest, Loja, Ecuador

Figure 3. - Species with the greatest volume in the woody component of the Huashapamba forest, Loja, Ecuador

Diametric structure of the Huashapamba forest

The diameter distribution has the shape of an inverted "J"; in diameter class I (5 to 10 cm) and II (10.1 to 15 cm) the largest number of individuals is recorded with 395 ind. ha-1 and 328 ind. ha-1 respectively (63.75 % of the total number of individuals recorded). Diameter classes XI (55.1 to 60 cm) and XII (> 60 cm) have 5 individuals in each class, with mature trees of Ruagea glabra, Clethra revoluta, Weinmannia rollottii, Schefflera acuminata, Abatia parviflora and Myrcianthes rhopaloides (Figure 4).

Figure 4. - Diametric structure of the woody component of the Huashapamba forest

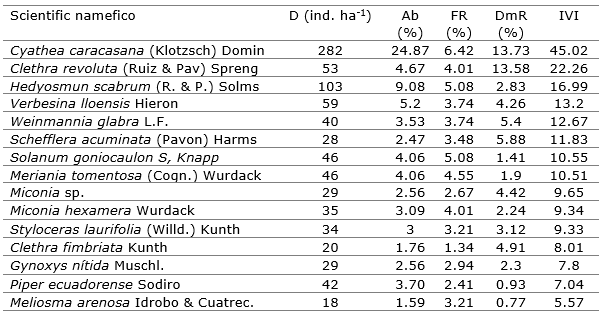

Structural parameters of the woody component of the Huashapamba forest

The species with the greatest presence in the forest are Cyathea caracasana, Hedyosmun scabrum and Verbesina lloensis, which are also the most abundant. Cyathea caracasana, Hedyosmun scabrum and Solanum goniocaulon are the most frequent species in the forest, while Cyathea caracasana, Clethra revoluta and Schefflera acuminata are the dominant species.

The species with the highest importance values were Cyathea caracasana with 45.02 %, Clethra revoluta with 22.26 % and Hedyosmun scabrum with 16.99 % (Table 4).

Table 4. - Structural parameters of the 15 main species of the woody component of the Huashapamba forest, Loja, Ecuador

Absolute Density (D); Relative Abundance (RA); Relative Frequency (RF); Relative Dominance (RD); Importance Value Index (IVI).

DISCUSSION

Floristic composition of the woody component

In Huashapamba, 54 species of 39 genera and 27 families were recorded, results dissimilar to those reported by Aguirre et al. (2017) in a permanent plot of one hectare in the Hoya de Loja, who report 45 species, 39 genera and 29 families; to Rasal et al. (2012) who evaluated two sites in Los Molinos finding 41 species, 33 genera and 25 families; and, at the La Antena site with 86 species, 67 genera and 41 families and, very different to that reported by Maldonado et al. (2018) in a tropical montane forest who found 81 tree species.

The Shannon index of 3.10 in Huashapamba indicates a medium diversity, a result similar to that reported by Aguirre et al. (2017) in the Hoya de Loja (3.16), a result that demonstrates the importance of the Huashapamba forest for the conservation of floristic diversity in the Saraguro canton and in the Southern region of Ecuador.

The families with the highest number of species in the Huashapamba forest are: Melastomataceae, Asteraceae, Solanaceae, Clethraceae, Cunoniaceae, Primulaceae, and Symplocaceae; results different from those reported by Aguirre et al., (2017) who recorded: Rubiaceae, Araliaceae, Asteraceae, Melastomataceae, Primulaceae, Lauraceae and Proteaceae. Similarly, Lozano et al., (2012) highlight families such as Rubiaceae, Lauraceae and Melastomataceae. Gentry (1995) and the Atlas of the Northern and Central Andes (2009) indicate Melastomataceae, Lauraceae and Rubiaceae as the most diverse families. Similarly, Alvear et al., (2010) indicate that the most ecologically important families were: Melastomataceae and Asteraceae in the Colombian Andes; and in the Peruvian Andes, according to Rasal et al., (2012), Asteraceae, Lauraceae, Melastomataceae and Solanaceae stand out. The data themselves have no similarity, but it is important to insist that, in the Andes of Ecuador, Colombia and Peru, the outstanding families are: Melastomataceae, Asteraceae, Lauraceae and Solanaceae.

Basal area and volume of the woody component

In the tree stratum, 1 134 ind. ha-1 were recorded, with a basal area of 30.24 m² ha-1 and volume of 215.86 m3 ha-1, values higher than those reported by Quizhpe et al. (2017) in this same forest, but in 0.75 ha of sampling, 434 trees, with a basal area of 13.37 m² and volume of 31.25 m3, this difference is due to the sampling area and that the sampled individuals are greater than 10 cm D1,30. Comparing with Yaguana et al. (2012) in the Tapichalaca forest there are differences in the number of individuals 544 trees ha-1 and medium similarity in basal area and volume: 25.68 m² ha-1, 255.24 m3 ha-1; and, with the Numbala forest shows difference with 1 091 ind. ha-1, 47.13 m² ha-1 of basal area and 651.89 m3 ha-1 of volume. These differences are probably due to the degree of disturbance and the structural difference of the investigated forests.

Diametric structure of the woody component

In this study, the first six diameter classes group 93.92 %, demonstrating that the forest is in the process of recovery, this coincides with what was stated by Aguirre et al. (2017); Yaguana et al. (2012), Aguirre et al., (2018) which indicate that the trees that make up this type of forest are thin and abundant, being scarce large individuals.

The diameter distribution of the Huashapamba forest adopts the shape of an inverted "J" (Figure 4). This is a frequent characteristic found in tropical forests, also indicated by Lozano et al. (2009) and Aguirre et al., (2017). The trend of the inverted "J" curve also indicates that the plant community is developing towards more advanced stages of growth and productivity, as stated by Lamprecht (1990), where abundant young individuals are replacing specimens that are in the senescent phase, confirmed by Aguirre et al., (2017); Yaguana et al., (2012); Aguirre et al., (2018) in studies in Andean forests in southern Ecuador.

Structural parameters of the woody component

The results of the densest and most abundant species in the forest (Cyathea caracasana and Hedyosmun scabrum) is particular only for this forest, as other studies, such as Aguirre et al. (2018), Yaguana et al., (2012), Aguirre et al., (2017) refer to other species in similar ecosystems. Regarding the frequent species Cyathea caracasana, Hedyosmun scabrum and Solanum goniocaulon, they exist in other studied forests, but they are not frequent. Cyathea caracasana, Clethra revoluta, Schefflera acuminata are dominant species in the Huashapamba forest. In Andean forests of southern Ecuador these species exist, but are not dominant, this is also corroborated by studies in the Hoya de Loja such as Aguirre et al. (2017) and Yaguana et al., (2012).

The ecologically important species by highest IVI are: C. caracasana, Clethra revoluta and Hedyosmum scabrum, results different from those reported by Aguirre et al. (2017) that indicate Alnus acuminata, Palicourea amethystina, Phenax laevigatus and C. revoluta as the species with the highest IVI in forests of the Hoya de Loja; to Yaguana et al. (2012) in Tapichalaca where the ecologically important species is Ficus insipida. While the plot in Numbala the ecologically important species are Retrophyllum rospigliosii and Prumnupitys hamsiana. The difference found is possibly due to the degree of anthropic intervention and maturity of the vegetation.

Endemism of the woody component of the forest

In the Huashapamba forest, six endemic species are recorded. Oreopanax andreanus, Verbesina pentantha, Miconia hexamera, Axinaea sclerophylla, Geissanthus vanderwerffii, are national endemics (León et al., 2011); and, Prumnopitys montana presents shared endemism, being found in several South American countries. These results are congruent with those reported by Gentry (1982) who states that the greatest richness in number of plant species occurs in the neotropics and especially in the Andes mountain range.

CONCLUSIONS

The floristic diversity is medium, expressed in the presence of 54 species of 39 genera in 27 families; 37 tree species and 17 shrub species. The most diverse families are: Melastomataceae, Asteraceae, Solanaceae, Clethraceae, Cunoniaceae, Primulaceae, and Symplocaceae.

The ecologically important species of the woody component of the forest are: Cyathea caracasana with the highest value of abundance and dominance, it is a tree fern scattered throughout the sampling plot; followed by Clethra revoluta and Hedyosmun scabrum, small species typical of Andean forests.

The woody species of the forest accumulate a basal area of 30.24 m² ha-1, and volume of 215.86 m3 ha-1; the species with the largest basal area is Cyathea caracasana and Clethra revoluta is the species with the largest volume; these data show that the forest is not susceptible to forest harvesting.

The diametric structure of the forest is plotted with an inverted "J", characterized by the abundance of thin individuals and few large and scattered trees, which shows that the forest is young and is in the process of self-recovery.

The structure, floristic composition of the forest and the presence of six endemic species justify the need to conserve this forest, as one of the last Andean forest remnants, located in the Saraguro canton of the province of Loja.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To the technical staff of the LOJA Herbarium, to the owner communities of Huashapamba that allowed us to work in their territory and supported us in the field data collection.

REFERENCES

AGUIRRE, Z.; CELI H. y HERRERA C. 2018. Estructura y composición florística del bosque siempreverde montano bajo de la parroquia San Andrés, cantón Chinchipe, provincia de Zamora Chinchipe, Ecuador. Arnaldoa 25 (3): 923-938. DOI: Disponible en: http://doi.org/10.22497/arnaldoa.253.25306

AGUIRRE MENDOZA, Z., AGUIRRE MENDOZA, N. y MUÑOZ, J., 2017. Biodiversidad de la provincia de Loja, Ecuador. Arnaldoa [en línea], vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 523-542. [Consulta: 9 julio 2020]. Disponible en: https://www.academia.edu/39841827/Biodiversidad_de_la_provincia_de_Loja_Ecuador_Biodiversity_of_the_province_of_Loja_Ecuador.

AGUIRRE MENDOZA, Z., CELI DELGADO, H. y HERRERA HERRERA, C., 2018. Estructura y composición florística del bosque siempreverde montano bajo de la parroquia San Andrés, cantón Chinchipe, provincia de Zamora Chinchipe, Ecuador. Arnaldoa [en línea], vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 923-938. [Consulta: 9 octubre 2020]. ISSN 2413-3299. DOI 10.22497/arnaldoa.253.25306. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S2413-32992018000300006&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es.

AGUIRRE, Z., 2019. Métodos para medir la Biodiversidad. 1ra. Ecuador: Universidad Nacional de Loja. ISBN 978-9942-36-127-1. Disponible en: http://entomologia.rediris.es/sea/manytes/metodos.pdf

BROWN, A.D. & M. KAPPELLE. 2001. Introducción a los bosques nublados del neotrópico: una síntesis regional. Págs. 25-40 en: M. Kappelle & A.D. Brown (eds.), Bosques nublados del neotrópico. Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad (INBio), Santo Domingo de Heredia. Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254778948_Introduccion_a_los_Bosques_Nublados

CUESTA, F., PERALVO, M., Y VALAREZO, N. 2009. Los bosques montanos de los Andes Tropicales. Una evaluación regional de su estado de conservación y de su vulnerabilidad a efectos del cambio climaìtico. Serie Investigación y 64 Sistematización # 5. Programa Regional ecobona intercooperation. Quito-Ecuador. Disponible en: https://www.bivica.org/file/view/id/320

FRANCO, M., BETANCUR, J. y FRANCO, P., 2010. Diversidad florística y estructura de los remanentes de bosque andino en la zona de amortiguamiento del parque natural de los Nevados, cordillera central colombiana. Caldasia [en línea], vol. 32, no. 1. [Consulta: 9 octubre 2020]. ISSN 2357-3759. Disponible en: https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/cal/article/view/36193.

GENTRY, A.H., 1982. Neotropical Floristic Diversity: Phytogeographical Connections Between Central and South America, Pleistocene Climatic Fluctuations, or an Accident of the Andean Orogeny? Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden [en línea], vol. 69, pp. 557-593. DOI 10.2307/2399084. Disponible en: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/8266.

GENTRY, A.H., 1995. Diversity and floristic composition of neotropical dry forests. Seasonally dry tropical forests [en línea]. Londres: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-511-75339-8. Disponible en: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/seasonally-dry-tropical-forests/diversity-and-floristic-composition-of-neotropical-dry-forests/4482CBC6F9FD8E01E0F6D30E9B7156A4.

HERZOG, S.K., MARTINEZ, R., JORGENSEN, P.M. y TIESSEN, H., 2013. Cambio Climático y Biodiversidad en los Andes Tropicales [en línea]. Francia: Springer. Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/245023891_Cambio_Climatico_y_Biodiversidad_en_los_Andes_Tropicales_Fenologia_y_Relaciones_Ecologicas_Interespecificas_de_la_Biota_Andina_Frente_al_Cambio_Climatico

JORGENSEN, P.M. y LEÓN YAÑES, S., 1999. Catalogue of the Vascular Plants of Ecuador [en línea]. Estados Unidos: Missouri Botanical Garden Press. ISBN 0-915297-60-6. Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258345280_Catalogue_of_the_Vascular_Plants_of_Ecuador.

LAMPRECHT, H., 1990. Silvicultura en los trópicos/ : los ecosistemas forestales en los bosques tropicales y sus especies arbóreas/ ; posibilidades y métodos para un aprovechamiento sostenido [en línea]. Alemania: Eschborn. ISBN 3-88085-440-8. Disponible en: https://www.iberlibro.com/Silvicultura-Tr%C3%B3picos-ecosistemas-forestales-bosques-tropicales/22864545783/bd.

LEÓN YÁNEZ, S., VALENCIA, R., PITMAN, N., ENDARA, L., ULLOA ULLOA, C. y NAVARRETE, H., 2011. Libro Rojo de las Plantas Endémicas del Ecuador [en línea]. Estados Unidos: Missouri Botanical Garden Press. [Consulta: 14 julio 2020]. ISBN 978-9942-03-393-2. Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318970039_Libro_Rojo_de_las_Plantas_Endemicas_del_Ecuador.

LOZANO, P., TORRES, B. y RODRIGUEZ, X., 2013. Investigación de Ecología Vegetal en Ecuador: Muestreo y Herramientas Geográficas [en línea]. Ecuador: Universidad Estatal Amazónica. ISBN 978-9942-932-04-4. Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282734548_Investigacion_de_Ecologia_Vegetal_en_Ecuador_Muestreo_y_Herramientas_Geograficas /link/561ab00808ae6d1730898ec2/download.

MALDONADO O. S., HERRERA HERRERA C., GAONA OCHOA T. Y AGUIRRE MENDOZA Z. 2018. Estructura y composición florística de un bosque siempreverde montano bajo en Palanda, Zamora Chinchipe, Ecuador. Arnaldoa 25 (2): 615-630. ISSN: 1815-8242 (edición impresa), ISSN: 2413-3299 (edición online). Disponible en: http://doi.org/10.22497/arnaldoa.252.25216

MORENO, C.E., 2001. Métodos para medir la biodiversidad [en línea]. Zaragoza: M & T Manuales y Tesis SEA. [Consulta: 14 septiembre 2020]. Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304346666_Metodos_para_medir_la_biodiversidad.

PERALVO, M. CUESTA, F. BAQUERO, F. 2013. Identificación de vacíos y prioridades de conservación en el Ecuador continental. Disponible en: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266146873_identificacion_de vacíos y prioridades_de_conservacion_en_el_ecuad or_continental

PHILLIPS, O., BAKER, T., FELDPAUSCH, T. y BRIENEN, R., 2016. Manual de Campo para el Establecimiento y la Remedición de Parcelas [en línea]. Perú: RAINFOR. Disponible en: http://www.rainfor.org/upload/ManualsSpanish/Manual/RAINFOR_field_manual_version2016_ES.pdf.

QUIZHPE W., VEINTIMILLA D., AGUIRRE Z., JARAMILLO N., PACHECO E., VANEGAS R., JADÁN O. 2017. Unidades de paisaje y comunidades vegetales en el área de Inkapirca, Saraguro, Loja, Ecuador. Revista Bosques Latitud Cero. V7 (1) pp. 103-122. Disponible en: https://revistas.unl.edu.ec/index.php/bosques/article/view/175

RASAL, M., TRONCOS, J., PARIHUAMÁN, O., QUEVEDO, D., ROJAS, C. y DELGADO, G., 2012. La vegetación terrestre del bosque montano de Lanchurán (Piura-Perú). Caldasia [en línea], vol. 34, no. 1. [Consulta: 14 octubre 2020]. ISSN 2357-3759. Disponible en: https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/cal/article/view/36419.

SECRETARÍA GENERAL DE LA COMUNIDAD ANDINA, 2009. Atlas de los Andes del Norte y Centro [en línea]. Perú: Comunidad Andina - CAN. [Consulta: 9 octubre 2020]. Disponible en: https://sinia.minam.gob.pe/documentos/atlas-andes-norte-centro.

YAGUANA, C., LOZANO, D., NEILL, D.A. y ASANZA, M., 2012. Diversidad florística y estructura del bosque nublado del Río Numbala, Zamora-Chinchipe, Ecuador: El "bosque gigante" de Podocarpaceae adyacente al Parque Nacional Podocarpus. Revista Amazónica Ciencia y Tecnología [en línea], vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 226-247. [Consulta: 14 octubre 2020]. ISSN 1390-5600. Disponible en: https://revistas.proeditio.com/REVISTAMAZONICA/article/view/172.

Conflict of interests:

The authors declare not to have any interest conflicts.

Authors' contribution:

Zhofre Huberto Aguirre Mendoza: Conception of the idea, literature search and review, instrument making, statistic analysis, preparation of tables, graphs and images, database preparation, general advice on the topic addressed, review and final version of the article, authorship coordinator, translation of terms or information obtained, review of the application of the applied bibliographic standard.

Leidy Cango Sarango: Literature search and review, instrument application, compilation of information resulting from the instruments applied, statistic analysis, preparation of tables, graphs and images, database preparation, Drafting of the original (first version), translation of terms or information obtained.

Wilson Quizhpe Corone: Instrument making, preparation of tables, graphs and images, general advice on the topic addressed, article correction.

![]()

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.

Copyright (c) 2021 Zhofre Huberto Aguirre Mendoza, Leidy Cango Sarango, Wilson Quizhpe Corone